Hi; I hope you’ve had a good week!

This week, Clayton Christensen died. He was most famous for his book on The Innovator’s Dilema, which has more going for it than ”disruptive innovation”; and for his influence on Andrew Grove, who turned around Intel in the 80s(Grove then wrote a book, High Output Management, which remains extremely widely recommended in tech circles for those who want to improve their management and leadership skills; it advocated quite early on for regular one-on-one meetings, for instance).

But Clayton Christensen was also beloved by students at Harvard Business School for the genuine interest he took in teaching, and he felt equally strongly about management:

Management is the most noble of professions if it’s practiced well. No other occupation offers as many ways to help others learn and grow, take responsibility and be recognized for achievement, and contribute to the success of a team.

I believe this to be true; especially in areas like research, where the stakes are high - new ways of advancing science! - and where management is not only in bad shape generally but treated with active suspicion (“going over to the dark side”). Many of us have given up the the day-to-day satisfaction of hands-on advancement of science to instead help other people have those achievements and that satisfaction, so that more of the right research computing and more science can be done. And so yes, god help me, there’s importance and nobility in that - or there can, and should, be.

Research computing is still a new enough field that we’re still figuring it out. Individuals are starting to professionalize around research software development (witness the formation of RSE groups), but the field as a whole can’t professionalize until there’s a cohort of professional research computing managers. Excellent individual contributors can’t do their best work if they’re led by professional managers who don’t understand research computing, so have them working on the wrong problems and interacting the wrong way with the research community; and they can’t work effectively if they’re led by researchers who haven’t yet been taught to be professional managers and so still assign work poorly, don’t set or enforce expectations, let issues fester, don’t help with career development, or can’t advocate properly for the team.

As a community we’re certainly not going to get that training from our institutions, so it’s up for us to teach ourselves.

I’m getting ready to start things in mid-February, and based on feedback I’ve gotten from you, I’ll be starting off focusing on five areas (and the link roundups will start to reflect that). In order of priority:

Managing Teams - As above: building the team, helping the people on the team have the most impact they can have, and helping them grow their career. Leaning on work from the tech, business, and nonprofit worlds, because our environment is like (and unlike) all of the above. Techniques, tools, best practices.

Product Management - The emphasis in research is around project management, since we’re funded through grants for projects. But we actually do product management in this field, which includes constant communication with customers(users and funders); communications and advocacy (which never ends; even when a product is ”done” and a success, if you want those lessons to be learned for the next time, you have to keep advocating), and prioritization across projects - program management.

Working with Research Communities - The purpose of research computing is the research, not the computing, and that means working actively with research communities to support their work, advocate for the role of research computing, and to help knowledge disseminate in both directions.

Data and Infrastructure Tools - Both sides of our field, research and computing, are moving incredibly fast, and it’s hard to stay on top of what might be relevant. I’ll try to help a bit here with context around new tools that are starting to be useful in a research computing context, including the occasional deep dive into something that’s already pretty well known in our community.

Research Software Development - How do you best build tools to solve problems people haven’t solved before?

If there’s specific topics you want to see in those areas, just hit reply and send me an email.

So enough editorial, on to this week’s links:

Hire Good Writers, ”Getting Real”, Basecamp

A short, thought provoking section from an interesting write up on building web applications by Basecamp.

“If you are trying to decide between a few people to fill a position, always hire the better writer…. Good writers know how to communicate. They make things easy to understand. They can put themselves in someone elses’ shoes. They know what to omit. They think clearly. And those are qualities you need.”

Breaking ties when hiring is genuinely hard, and I’m going to take this suggestion seriously when the next opportunity rolls around.

On being “technical” as an engineering manager, Sean Voisin

How technical do you have to be to be a technical manager? I think this blog post has the right answer; ”enough”, where enough will depend on what your team is doing and what your role is on the team.

You have to be able to make sure the team’s doing the right work and progressing satisfactorily, but that’s a different kind rather than a different amount of technical knowledge necessary to actually do the work. For us it will require a certain level of subject matter/domain science literacy as well as staying on top of what other teams are doing and using to solve nearby problems.

Google Cloud Certified Fellow: Hybrid Multi-cloud

Relatedly, this strikes me as interesting: we’re now starting to see certifications for technical managers, and not just for the people doing the work and implementing the solution. Some of these will likely tend to be vanity exercises - true for all certifications I suppose - but some will be valuable. Is there any techincal training (online or otherwise) that you’ve found really useful in your current role managing?

Do Introverts or Extroverts Make Better Leaders? Wally Bock

I don’t think it’s controversial to suggest that the population of people who have chosen (a) research and (b) computing for a career tend to be introverts, and that can make the transition to managing other human beings a jarring transition. But managing well is a set of skills, and there is no one who finds all of those behaviours - seeing the big picture, sweating the details, working closely with people, working closely with abstractions (and all simultaneously!) - immediately natural.

“When looking at CEOs who met expectations, we found no statistically significant difference between introverts and extroverts. High confidence more than doubles a candidate’s chances of being chosen as CEO but provides no advantage in performance on the job.”

While that’s very nice to hear, there’s something else here - those of us in the research computing field probably aren’t aware of studies like where that came from:

It’s based on their review of 17,000 leadership assessments.

There is actually a lot of data on the basics of good management, lots of which comes from quantitative studies at single large organizations (so where a lot of other variables are held constant). It’s noisier data than in say astronomy, because between-people variability is larger than that between stars, but that just means that you need large N. The basic low-hanging fruit of things people can do to manage well are not controversial or in serious question; people use (and argue over) different techniques to do the same basic things, but in the end you need to build good, trusting, working relationships with and between your team members, set consistent expectations and give constant feedback against those, help team members develop needed and desired skills, and give them increasing responsibilities. Our context may differ from manufacturing jobs, which matters, but the basics remain.

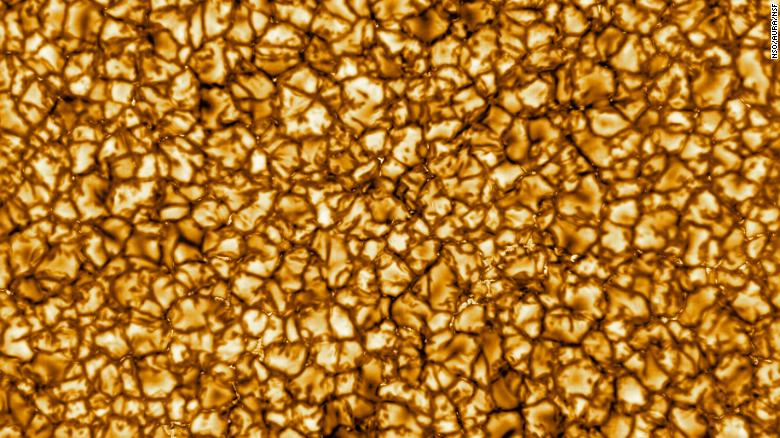

Hey, you know those highest resolution-ever pictures of the sun that have circulated the last couple of days?

(Allow me to nerd out for a second, because this kinda used to be my jam - You can see a movie of this here. What you’re seeing are convection cells, exactly like what you can see in a cup of tea or coffee in a very hot mug - dairy helps for contrast - or you can use soapy water and a pie plate. Well, exactly except that these are nuclear powers and the size of Texas. But fluid dynamics is scale-invariant!)

Anyway, those pictures were taken by the Inouye Solar Telescope which has three early-career research ’ambassadors’ to help others use its data:

https://twitter.com/alexwitze/status/1222595040695861249

https://twitter.com/alexwitze/status/1222595040695861249

I love this for a few reasons. Firstly, it’s clearly good for science - ensuring that as much science gets done by as many people as possible using the data which came from this major investment. Think how this would have looked in a grant application to the reviewers - this would have been a tiny fraction of the total spend, but it showed a real commitment to making sure that the funders’ investment led to as much impact as possible.

Secondly, it’s such a research computing move - helping researchers make use of complex noisy data sets that require a lot of specialized processing? Yeah, that kinda sounds familiar.

But finally, it’s such a product management move. Thinking like a project manager would mean focussing on timelines, deliverables and efficiency; getting the telescope up and running and generating output - and efficiently here would mean focussing on those researchers who could use the data on their own. Advocacy and community relations are over once the project is funded. But if you are focussed on the product - the science coming from the telescope’s data - you’re working with the community, making sure there are strong connections being built and maintained, working with late adopters to ensure they can be onboarded to the data set. This is the science experiment equivalent of the big commercial cloud vendors having developer relations teams, and it’s terrific to see.

If you build it, they will come…but then what? Facilitating communities of practice in R, Kate Hertweck

A lot of research computing teams I’ve seen have started regular training sessions for researchers; sometimes on a specific area, sometimes as ”Tech Talks” with varying topics. The model is generally one of having the technical team teach the researchers things, which is good and valuable but a little limiting and not really sustainable - you have to keep coming up with topics, teaching them, and hoping they stick. What would ideally happen is that the technical team would facilitate a self-sustaining community of researchers interested in computing teaching themselves, with input from the technical team still happening but not being the only form of instruction.

At Fred Hutch, “The Coop” has had good success with this, and Kate Hertweck, as bioinformatics training manager, has been one of the leaders of this effort. The slides give an overview of their work, and you can see how it looks in practice at the Coop’s website.

A little bit of docker content and database content this week (but not docker and databases, because that’s a whole separate topic…)

If like me you like to wrestle with the guts of something before being confident you have an understanding of it, Alex Ellis shows you how to build docker images without docker.

Relatedly, Ciro Costa has a deep practical look into overlayfs, which is the (under appreciated) layer which makes Docker images possible; but for what it’s worth I think it’s better to start with Julia Evans’ How Containers Work - Overlayfs. It took me a while to get used to her style, but her explanations are always so good - I never read something of hers without learning something new, even on topics I’m pretty familiar with. Picking just the right worked example to demonstrate something is a real art.

Finally, be careful of just blindly following advice; if you’re packaging something built using an interpreted rather than a compiled language, using Alpine base images for small containers may not be the right thing to do.

More on the application side, a paper just released The Rockerverse: Packages and Applications for Containerization with R goes through the standard docker image repository for R and catalogs what they are actually used for and how, which is always interesteing to see.

The Rise and Fall of the OLAP cube, Cederic Chin

The rise of columnar-store databases for analytics processing (OLAP) has been a terrific thing for research computing; real databases that you can do real analyses directly on instead of having to always pull data frames out of a row-based relational database and do calculations in memory. They’ve gotten so good that ”OLAP Cubes” - precomputed fine-grained aggregations that let you do foreseen queries extremely quickly - are starting to go away - or are they? I’d argue that in research computing, nothing useful actually goes away, it just changes form or lies in peaceful slumber until needed again; I’ve seen people take analytical databases, precompute a bunch of things, and stuff them in MongoDB catalogs for rapid aggregation. It may not be a cube, but it is very much the same idea.

Four Data Sharding Strategies We Analyzed in Building a Distributed SQL Database, Karthik Ranganathan

The other way to make queries fast, of course, is with sharding; different approaches favour different use cases. This is a nice overview of four approaches - algorithmic, linear hash, consistent hash, and range sharding. For their purpose there’s two clear winners, but a lot comes down to whether or not you know ahead of time what access patterns are going to be like.

On Pair Programming, Birgitta Böckeler & Nina Siessegger

A great description on the hows and whys of pair programming, a technique I don’t see very often in research software development (though giving how subtle some pieces of what we work on are, it might be useful).

There’s two big advantages of pair programming - knowledge transfer/collective code ownership (at least two people know how some piece of code works), and code quality (two people’s input is better than on). (It can have advantages for helping the team learn to work together, but that can cut the other way too).

Of the two I think knowledge transfer is probably more important - a piece of code that only on person understands is going to get quite brittle over time.

Even if pair programming doesn’t seem like a good match for your team, the material pairs really nicely with some of Chelsea Troy’s posts on pull requests and commit messages as a way of doing distributed, asynchronous collaboration - pair (or more) programming. It’s not enough to simply justify the change being made; the goal in Chelsea’s model is to get some of the advantages of pair programming without requiring synchronous and possibly in-person collaboration.

(And it turns out you can easily give (some) credit for peer programming in git, which I didn’t know).

Types Can Be Like Tests, Andrew Huth

A reminder that in dynamically-typed programming languages that do allow some kind of typing hints (like Python), adding those hints as the code gets mature is a way of implementing a particular test suite of lots of small low-level tests; the tooling is even good enough now to do some static checking.

Also in Python, there a number of deprecations that are turning into errors very shortly; heads up.

In Canada, CANARIE (the organization running the national research & education network) is having a funding call to support the hiring of research software development teams of three people for almost three years at up to six institutions, with the intent for the teams to support research efforts broadly across the institution. Deadline: March 17, 2020

The First US-RSE Association Workshop, 21-22 April, Princeton

Some pretty high-profile jobs this week; want to lead the visualization studio at Goddard Space Flight Centre?

Computer Scientist, AST, Data Analysis - Goddard Space Flight Centre, Greenbelt MD

This position will be the lead for the Scientific Visualization Studio (svs.gsfc.nasa.gov) located at the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC).

ESnet Director of Systems and Software Engineering - Lawrence Berkeley National Lab, Berkeley, CA

Energy Sciences Network (ESnet) at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL) is looking for a Director of Systems & Software Engineering to lead multiple managers and technical teams in building ESnet’s next-generation network software service portfolio.

Research Computing Architect, University of Chicago, Chicago

Responsible for the design, implementation, and maintenance of new and existing applications, systems architecture, and network infrastructure.

Head of Research Computing, University College of London, London

With full responsibility for five HPC platforms totaling over 40,000 cores you will lead a technically strong team, helping them to continually improve delivery of HPC services.

Head of High Performance Computing & Grid Services, HSBC, London

This team manages and develops the service for highly intensive calculations and memory bound problems for pricing, trading and increasingly accurate risk management of diverse and complex portfolios, while also supporting the Global Banking and Markets (GB&M) business and Risk function.

Advanced Computing, Mathematics & Data Division Director, PNNL, Richland WA USA

The Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) is seeking a dynamic scientific leader with a national and international reputation and record of accomplishment to serve as the Director of the Advanced Computing, Mathematics & Data Division (ACMD).

Head of Services Delivery for Big Data and High Performance Computing, Atos, UK

Ongoing development of services, in conjunction with internal and external product and service providers and in alignment with the Atos BDS Service Portfolio. (e.g. Big Data, HPC, High End Platforms).

Director, Research Computing, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

The Director of Research Computing provides technical services for campus students, faculty, staff, and external collaborators through University Information Technology Services (UITS).

Senior Research Computing Analyst, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada

Responsible for the design, implementation, and maintenance of new and existing applications, systems architecture, and network infrastructure.Ensures operation and security of all servers and networks

Sr Software Engineering, HPC/Parallel Distributed Computing, KLA, Milpitas CA

With over 40 years of semiconductor process control experience, chipmakers around the globe rely on KLA to ensure that their fabs ramp next-generation devices to volume production quickly and cost-effectively.

Research Computing Technician - Dalhousie, Halifax, NS, Canada

Leads the local Dalhousie HPC team by assigning university related tasks, and evaluating work

And that’s it for another week. As things start in mid February we’ll have more frequent emails but the individual emails will be shorter (I promise); I hope this wasn’t too much of a slog.

Have a great weekend, and good luck next week with your research computing team,

Jonathan