Hi, everyone:

I hope you’re doing well! I have two questions for you.

This week kind of got away from me - it’s been an exciting couple of weeks, with two new team members joining and our project getting ready to take on new responsibilities - but it means that the final instalment on research computing hiring will be delayed until next week.

So I’ll ask two question that I was going to ask at the end of the series.

First - I was starting to feel that the article plus the roundup was kind of unwieldy. (That’s why I started adding the ‘skip to the roundup’ link). Between the article and the roundup, we were starting to get up to 5000 words - and that’s not even counting the job postings. Even the roundup alone seems like it might be too many words sometimes.

So, what do you think? Should I split them out into two days posts - say new content on Monday, link roundup on Friday - with the option to subscribe to either to both? Or just keep on with how they are? Any other suggestions?

Second question - What should be next for the article content? I have my own topic list:

But I’d very much like your suggestions for topics - or for other features (enough time may have passed and new members joined to start up AMA - Ask Managers Anything - again).

So let me know what you’d like to see - as always, suggestions, feedback, and comments are greatly welcomed. Just hit reply or email me at jonathan@researchcomputingteams.org.

But for now, the roundup!

Series: Unpacking Interview Questions - Jacob Kaplan-Moss

This series of questions ties in very nicely with last week’s discsussion of evaluating against requirements. Kaplan-Moss has five interview questions that he covers - maybe they’d be good for your roles, maybe not - with very carefully thought out rubrics for each:

Getting to this level for your own interviews will take a lot of work, and may never happen for some requirements if, as for most of us, your requirements change more rapidly than you hire. But this standard is an excellent one to aspire to, whether your approach to evaluating against a particular requirement is an interview question or a skill-testing simulation of work product like a technical test. What constitutes a good response, and a poor one - and if you can’t clearly express an answer to that, is it really a good evaluation method? How should you follow up on a response/submission?

Engineering Productivity Can Be Measured - Just Not How You’d Expect - Antoine Boulanger, OKAY

A while ago we had a flurry of “measuring developer productivity” articles, mainly pointing out that the idea was a bit misguided.

There’s a management book, “How to Measure Anything”, which I think of as “Error Bars for Business Types”. Fine book as far as that goes; not really for us as an audience. But one point that book made stuck with me - as managers, the purpose of a measurement we make is to inform a decision, and thus action. We don’t measure “just to keep an eye” on something.

I think when research computing managers daydream and imagine measuring team member productivity, the tendency is to picture some dashboard we can look at every so often while we’re doing our own stuff, and only switch into manager mode and intervene when the dashboard flips from green to yellow. “Hey, Jason, it seems like there’s some kind of problem. Tell me about it”. It’s a lovely thought and just completely divorced from the reality of managing a team in research computing, where we have to constantly talk and work with people - team members, stakeholders - to understand what’s going on, find out what’s needed, remove blockers, and to help everyone stay pointed in the same direction.

For individuals, there’s nothing much more you can do than routinely set goals with team members, and then together assess whether or not those goals were reached, why, and what can be done differently in the future. It’s labour intensive and requires subjective judgement and that’s about all there is to it.

As Boulanger points out, however, there absolutely are useful productivity measures we can keep track of and act on - at the team level. The idea is to track things that are slowing the team down - is tooling inadequate? Are processes leaving tickets or code review requests sitting idle for too long? Are people’s days sliced up into too many chunks with meetings? - and do something about it as a manager.

Boulanger suggests that we:

And turn these questions into a modest number of metrics to focus on and improve. Of course, this flips the script on what some managers in tech imagine the purpose of the productivity metrics are for. Rather than turning them on the team members (“You’re only scoring an 18.3 not he productivity meter! Productivize more!”) it means there’s work for the manager to do. Such is the reality of our job.

Tough Love for Managers who Need to Give Feedback - Lara Hogan

Stop Softening Tough Feedback - Dane Jensen and Peggy Baumgartner, HBR

Both Hogan and Jensen & Baumgartner’s article tell us not to soften our critical feedback. If we’re not frankly telling our team member how they’re not meeting expectations, then how can we possibly expect anything to change? And if we’re not trying to change future outcomes - by learning that the expectation wasn’t reasonable, or by having the team member meet the expectation in the future - why are we even having the conversation?

Hogan adds another four points:

Jensen & Baumgartner focus more specifically on “sandwich feedback” - softening critical feedback by surrounding it with positive feedback. There’s actually data on how poorly that works - it’s transparent and frankly a little condescending. You should absolutely be giving lots of positive feedback as well as critical feedback, so that your team members know that you see the times they meet or exceed expectations as well as when they don’t - but you give the positive feedback as it arises, not as a diluent for corrective feedback.

They also recommend, after pointing out the behaviour/observation that’s causing the feedback and the impact the failure to meet expectation is having, you tell them what you’d like them to do next. I’d caution about that - it’s not what they mean, but it sounds like “you should do it this way in the future”, which isn’t what you want. You don’t want to be prescriptive about how your team members do things, you want to be clear about the expected outcomes and let them have the choice about how to get there.

The skill of naming what’s happening in the room - Lara Hogan, LeadDev

There are a number of meeting skills which can certainly apply to manage a team but are powerful skills to have in other contexts, too. In what may be a first for the newsletter, Hogan appears twice in one issue with articles from two different venues. In this LeadDev article, she describes one powerful and under-used skill - actually describing what’s happening in the meeting. An example from the article:

‘Hey, let’s just take a second to check in: it feels like maybe we are going in circles on this.’

As people partly in (often academic) research and partly in tech, we as a population are disproportionately … less than enthusiastic about talking about feelings or individual reactions to stuff. Life of the mind, and all. That’s what makes this a bit of a superpower; “I get the impression the software developers are less enthusiastic about this idea, is that right?” or “The research team has repeated that point a couple of times - I get the sense they feel like it’s not being fully understood, is that a fair interpretation?” can completely un-stick a meeting which has fallen into a frustrating rut.

Even if you’re pretty junior in the context of some particular meeting and not feeling comfortable calling these things out, just learning to make these observations and put them into words in your own mind is an incredibly powerful skill to develop.

Mailbag: Building alignment around a new strategy - Will Larson

This was written in the context of setting a technical strategy within a technical organization, but it works just as well in a context where you’re working with stakeholders and researchers about a product or project strategy.

The approach Larson describes will be familiar from the discussion about “change management” and stopping doing things in #58 - there’s no way around it, it’s labour- and time-consuming. You have to first make sure everyone agrees on the problem, then build towards a solution, and shop that around getting input.

Most of us aren’t working with communities of a size where a working group makes sense - it’s our job to put together an initial solution proposal (or a couple of options), then pre-wire that information, iteratively gathering feedback, getting ready for a presentation where a solution is proposed. But the basic approach is the same. If it sounds like a lot of work, it is! Getting wide agreement about something new, or even worse a change to something old, is genuinely difficult, there’s no way around it.

UKRI champions technical careers in research and innovation - UK Research & Innovation

UKRI has developed an action plan that “will ensure technicians are recognised for their essential role in research and innovation and supported to develop skills and careers. “

Technicians are different than research computing staff, but not so different that problems with career paths, career development, fair and stable remuneration, issues with being the lone “pet” specialist embedded in a research group, etc. are unfamiliar. Increasingly these research support roles are being recognized as being key to the larger research endeavour, and so we can watch announcements like these with some interest, and make the same arguments to funders in other jurisdictions for our teams needs in research computing.

6 ways to RUIN your logging - Jonathan Hall

Logging is an important part of moving research software up the technological readiness ladder. For a tool to be usable in a wide number of contexts while remaining supportable, deliberate logging makes addressing user problems much easier.

This article discusses ways development teams can make their logging more useable for all consumers of logs - users, operators, and developers, and more maintainable to help keep the logging useable:

One point here I haven’t really seen before is a pretty strong and convincing take on what makes for apporpriate log levels:

Developers spend most of their time figuring the system out - Tudor Girba, feenk

Writing good code by understanding cognitive load - David Whitney

ARCHITECTURE.md - Aleksey Kladov

Girba points us to a recent article: Xia, Bao, Lo, Xing, Hassan, & Li (2018), **Measuring Program Comprehension: A Large-Scale Field Study with Professionals*,* IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering that looked at 78 professional developers during over 3000 hours of their work and found that 58% of their time was taken up by comprehending a code base; we can infer that work that goes into making code bases more comprehendible improves developer productivity.

Girba’s team has a specific solution to this, but in general, we should work on reducing code’s cognitive load and easing comprehension. Whitney argues that this is a key consideration:

There isn’t really such a thing as “good code” – there’s just code that works, that is maintainable, and is simple. There’s a good chance you’ll end up in a better place if you spend time and effort making sure the cognitive load of your application is as low as possible while you code.

Whitney doesn’t argue for any silver bullets; just a nuanced understanding that abstractions and refactoring have costs as well as benefits for comprehension and cognitive load. Abstractions help by communicating expectations, but moving pieces of code around makes code harder to understand (and in the Xiv et al paper, navigation of a code base is next at 24% of developer time!) It’s a careful and thoughtful piece, and doesn’t lend itself to a short summary; it’s worth reading if the topic interests you.

Kladov makes a simple and implementable pitch for open source (and presumably proprietary) code bases as soon as they start hitting 10k lines of code - along with a README and CONTRIBUTING document, add an ARCHITECTURE document which spells out big picture components, boundaries between components, invariants within components, and cross-cutting concerns.

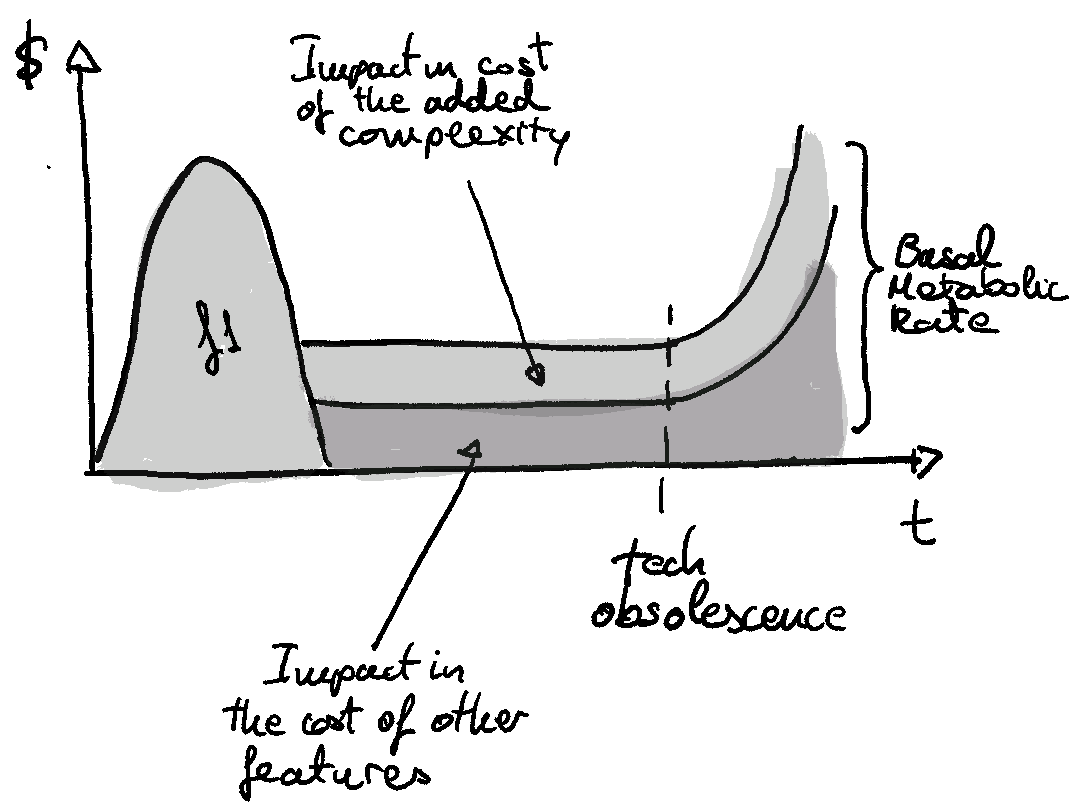

The Basal Cost Of Software - Eduardo Ferro Aldama

We all know that being responsible for software comes with a low-level, ongoing maintenance cost, but it’s easy to forget. Aldama casts the idea in terms of a “basal metabolism” of a piece of software, which requires a base level of energy to sustain - which remains flat for a period of time until changes in underlying technologies the code relies on cause the basal rate to grow significantly.

How to Tell a Client How Bad Their Code Is? - Nicolas Carlo, Understand Legacy Code

As is often the case, Carlo’s weekly article on legacy code is relevant to those who have been handed some research software that needs help moving up the next rung of the technological readiness ladder, or just to get it back working again. He gives us some tools to guide us through conversations that start with being asked “why can’t you just…”, including:

Livermore’s El Capitan Supercomputer to Debut HPE ‘Rabbit’ Near Node Local Storage - Tiffany Trader, HPCWire

Trader writes up a good summary of a talk by Livermore Computing CTO Bronis de Supinksi, describing some fascinating details of the upcoming LLNL “El Capitan” system, to be delivered by HPE. The main focus of at least the article the near-node local storage system, where compute nodes are connected by PCI(!) to nearby 4U Rabbit nodes, which have a bunch of SSDs, and a storage processor:

“If we think about how Rabbit works, this is really like building a little nest of PCIe networks within the larger system,” said de Supinski.

With the local-ish connections to compute nodes and a significant amount of CPU available at the storage, this could be used number of different ways, including as a a “transient Lustre file system” which would then stage data out to spinning disk, for N-to-M checkpoints, or for staging data files or even libraries out to compute nodes for faster startup or loading of data. Also, containers can be run on the storage nodes as part of the user jobs, due to the use of Flux as a scheduler

The increasing complexity of large-scale storage - including the scheduler, containers, webs of local PCI networks within a larger cluster - is really exciting to watch, and its interesting to see how the tools being built for storage will work with other forms of composable systems. (Especially with PCIe 6 getting ready to roll out!)

Running Nomad for home server - Karan Sharma

With Nomad now stable and at 1.0, we’re starting to see more tutorials for it - including this one where Sharma describes not only how to get started, but the experience of migrating away from Kubernetes.

If you have to provide cloud-native infrastructure as a service to clients, Kubernetes (or depending on model, OpenStack) will still be a (the?) viable solution - but for anything short of that, once you’ve outgrown Docker Compose/Swarm, Nomad is an increasingly viable solution for handling individual applications, and even running batch or recurring jobs.

| Designing effective criteria for assessing engineering candidates equitably; Unlock engineering talent through equitable hiring - 24 February, 9am PT | 12pm ET | 5PM GMT, Free |

A workshop by Karat, hosted by LeadDev, on equitable hiring through careful assessment of candidates - very much on topic for the past month.

Rice Oil & Gas HPC Conference - Talks 5 March, 8-4 CST, workshops 12, 19, and 26 March 12, 19, and 26 March, Free

The audience of this HPC conference is Oil and Gas industry-based, but the topics - the near-term future of HPC, porting to accelerators, HPC in the Cloud, systems management best practices - will be of interest to a broad range of HPC practitioners.

EuroHPC summit and PRACE Days 2021 - 22-26 March, Free

A full week of talks on the EU HPC ecosystem, work in various industries and disciplines, COVID projects, and workshops.

ENIAC was announced 75 years ago this week.

A list of software-development-relevant services that offer a free tier.

Free cyber security learning/training resources.

Lesser-known but useful advanced (intermediate?) git commands.

Relatedly - in praise of git worktrees.

Not news to this audience, but maybe some of the trainees you work with would take it from Nature that there are reasons for researchers to love the command line.

With so much written about doing good open research in computing, I think it’s good and important that there are very simple “best practices”, “good enough practices”, and now “barely sufficient practices” in scientific computing to provide an accessible on-ramp for researchers new to making their software available.e

I do think an underexplored approach for large-scale IoT data collection for research projects are solutions like Cloudflare’s or now fly.io’s increasingly capable “at the edge” compute options.

For me, a big driver for SaaS solutions for to-do lists or writing tools was being able to have access to the stuff at work and at home. If we’re working from home indefinitely, is that even a thing any more? Imdone is a Trello-alike and Ghostwriter is a blogpost or other editor, all based on local directories of Markdown files.

Really interesting looking free ~300page book - an introduction to ML specifically focussed on prediction and decision support.