Hi, all!

A slightly short newsletter today, as I finally claw my way back onto the Friday schedule.

One community update from last week - there was a fair amount of interest in using the Rands Leadership Slack as a pre-existing place with a large (>20,000!) leadership and management community as a place to discuss topics of interest. There is now a #research-computing-and-data channel, with sixteen members so far - some newsletter readers, but also some who had already been on rands and quickly joined once the channel was created. If that sounds potentially of interest to you, we’d love to see you there!

Otherwise this week I’ve mainly been continuing to offboarding myself from my current job. The coming week is my last (and I think the final 1:1s are going to be tougher than I was anticipating). Most of the knowledge transfer has now been done — although to wrap it up, next week I’m giving a demo of a key piece of technology to the team. Manager does a demo! What could possibly go wrong? This week there’s been a lot of 1:1:1s, with a team member and either I and my replacement, or the replacement and our boss, about transfer of responsibilities or “what’s next” conversations.

One thing I’ve been doing in my last two one-on-ones with team members is going over our work together, and putting together letters of reference which then get also turned into LinkedIn recommendations. Hopefully the team members will stay happily part of the team for a long time to come, but being a reference is a key responsibility of a manager or supervisor, especially in academia, and I want to make sure that I get these things written up while our work together is fresh in our mind. Having a record from previous quarterly reviews and one-on-one meetings is a huge help in putting these letters together. Also, routinely distilling information from those meetings into the cover sheet of the one-on-ones was a huge help when handing over managerial responsibilities to my replacement.

Like so many things in management, the preparation that is making this handover easier — one-on-ones, quarterly reviews, keeping meeting notes, distilling them every so often — was not difficult, complex, or even very much work. It just took a bit of discipline to keep routinely doing the little tasks that help things run smoothly. And that, after all, is all professionalism is. Our team members and our research communities deserve research computing and data teams that are managed with professionalism.

So, what’s next? As you know, supporting research computing and data teams in their work to, in turn, support research, is very important to me. Starting Feb 21st, I’ll be doing just that but from the vendor side of things; I’ll be a solution architect for NVIDIA (and the second NVIDIAian I know of on the newsletter list - Hi, Adam!). After five and a half years working on single project, I’m really excited to be working with a large number of research groups and teams again - a bit like my work from long ago at an HPC centre, but wearing a different hat. I’m a bit nervous about the different expectations and pace of the private sector, but genuinely pumped to be playing with a large number of different technologies to support groups trying to tackle a large number of different problems.

What does this mean for the newsletter? Not a lot of change, really. NVIDIAs policy on social media (including newsletters) is very reasonable; the changes are really going to come from me wanting to be (and be seen to be) even-handed and balanced.

I’ve been steering away so far in 2022 from commenting on specific new technologies coming out, to see how that goes; and the newsletter is actually better for it. There’s a zillion places you can go for the latest “speeds and feeds” update; that’s not what this newsletter has ever been about, even though it would slip in sometimes. So there won’t be any conflict of interest around new or updated product announcements; they won’t really come up here.

If there is some item that in some way is related to NVIDIA that I think is genuinely important for our community to know about, I will link to it in the roundup, preferably an article from a third party, but will refrain from commenting on it; and I’ll go out of my way to make sure any such links are balanced by related links touching on news from other vendors, which will also go without comment. But I expect that to be a pretty rare occurrence.

Other than that, I’ll probably have some kind of disclaimer in the newsletter — I work for NVIDIA, but opinions expressed here etc etc — but there won’t be drastic changes.

And with that, on to the roundup!

What is the cost of bioinformatics? A look at bioinformatics pricing and costs - Karl Sebby

This article is important to ponder even if your team’s work falls completely outside of bioinformatics.

Service delivery models gets very little discussion in our community despite its importance. That’s a shame! It’s a pretty key part of how we interact with research groups. The delivery model determines how easily communicated and sustainable providing the service is, even if there isn’t any kind of cost recovery. How the service is delivered is a key part of the service itself.

Here Sebby investigates the variety of delivery models and prices for the analysis of next-generation sequencing data. This is a pretty specific kind of problem, typically with a clear underlying task and well-defined best practices, and yet it’s still an interesting example. There is both the compute cost and the people-time cost, and it requires expertise and close interaction with the research group.

Even with this extremely well-scoped offering, there are at least four different delivery models described:

There are pros and cons to each approach; they appeal to different potential clients, who have different expectations and different kinds of expertise available internally. The hourly rate is safest for the service provider, but is riskier for the client (how do I know how much will this cost in total?). “Productized service” is easiest for the casual researcher to understand, and transfers some of the risk to the service provider (what if this sample’s data is especially low-quality and takes longer to process?). On the other hand this approach makes it much easier to “sell” a large number of the services, and over time it should average out. Set-up-some-infrastructure is nice and readily automated for the service provider; it’s more work for the researcher but may make a lot of sense for a group that has many samples to run and its own internal expertise. And if your group was doing a lot of similar tooling setup for a lot of different clients, it might make sense to become a platform of some sort.

To be clear, this sort of service design thinking does not hinge crucially on money being charged to cost centres. How researchers know what you can do for them, how that work is packaged up into deliverables, and how do they know what it will ask of them in terms of effort and turnaround time are important questions to work through even if the service is “free”.

And if it’s not free, look at that range of prices and rates quoted - productized services for the same service range by factors of 2-3, in one case 7x; hourly rates vary by a factor of 6. And yet all of these service providers are going concerns. Maybe always being the cheapest option available isn’t the only feasible choice?

Has your team put some thought into different approaches to service delivery? Different “business models”, whether or not money changes hands? What did you consider, and how did it go? Let me know - email at jonathan@researchcomputingteams.org, or just hit reply.

Prioritization, multiple work streams, unplanned work. Oh my! - Leeor Engel

Engineering managers: How to reduce drag on your team - Chris Fraser

Research computing shares with smaller, newer organizations like startups a very dynamic set of demands, requirements, and work. This distinguishes both from work in teams at many large mature organizations or in IT shops. The dynamism makes prioritization and focus especially important.

Engel describes some principles for managing work in such a dynamic environment:

Fraser’s article is superficially on a completely different topic. We’ve talked before (#39, #76) about how the key to speeding teams’ progress isn’t about urging them faster so much as removing things that make them go slower. But key items Fraser points out that cause drag are the same things Engel urges us to work on:

Other items - improve trust with regular one-on-ones, and implement the tooling the team needs - are the bread-and-butter of management work.

Levels of Technical Leadership - Raphael Poss

Management is hard, and time consuming, and takes one away from hands-on work. Not everyone wants to do it, even as they grow in their careers.

It’s becoming common understanding, even in academic circles, that there’s a need for a technical individual contributor career ladder — a path for growing in technical responsibility and impact without taking on people management responsibilities.

But there’s an ambiguity there. Management, for all its challenges, has the clarity of a career step-change. HR records someone as reporting to you, or they don’t; more bluntly, you can fire someone or you can’t. There’s no gradations of in-between. What does “increasing technical responsibility” look like?

If your organization doesn’t have such a track yet, or is reconsidering one, this article by Poss gives a nice overview. It explains how the analogue nature of “increasing responsibility” allows for organically increasing responsibilities over time. There is a career ladder with expectations, which is consistent with what is described in this paper and blog post (mentioned in #94) summarizing how NCSA, Notre Dame, and Manchester’s RSE groups work or plan to work.

The stay interview is the key to retention right now. Here’s how to conduct one - Michelle Ma, protocol

The State of High Performing Teams in Tech 2022 - Hypercontext

We’ve talked a little bit about the challenges of retaining team members these days. Most of us haven’t seen a huge exodus, but I’ve certainly seen several key members of various teams move in the past couple of months, including one on our own.

In the first article, Ma talks to Amy Zimmerman on “the stay interview” - kind of an exit interview, but while your team member is still with you. Why wait until your team member leaves to find out what was wrong?

Keeping track of how happy people are and what they’d like to be doing is a good topic to routinely bring up in 1:1s and quarterly reviews (#68), but Zimmerman goes a little deeper with some of the questions:

Some of the others should really come up in first one-on-ones (Laura Hogan has a good set of first 1:1 questions), but are good to keep coming back to.

It may feel scary to explicitly bring up questions like “what might tempt you to leave”, but the fact is your team members are almost certainly not going to retire from their current job with you. The more frankly and frequently you can have these career direction conversations, the longer you’ll be able to align the work they do with their personal goals.

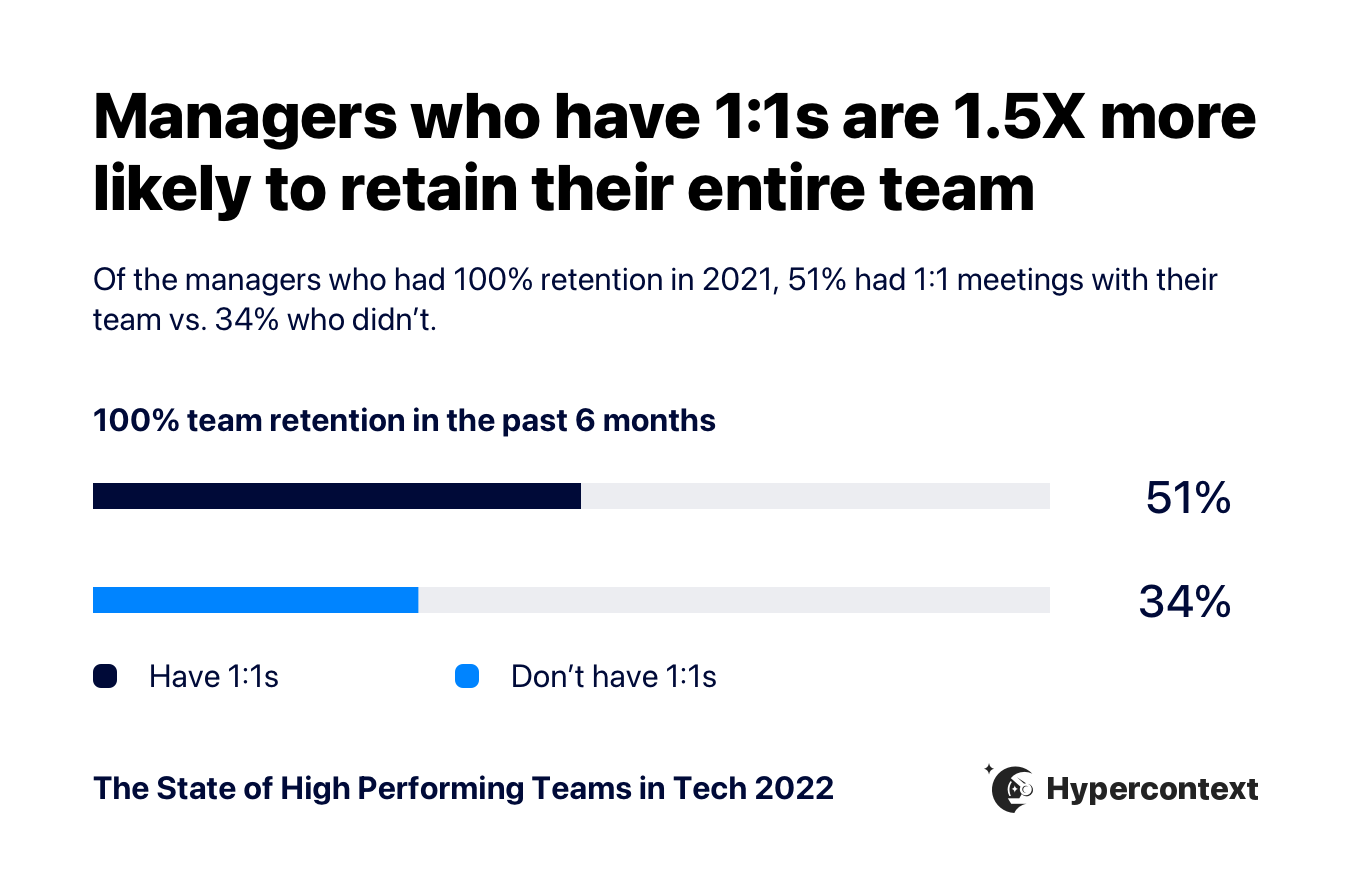

In the second article, the folks from Hypercontext did a survey on high-performing tech teams, and there’s some good stuff in there, most of which won’t be surprising to long-time readers of the newsletter (routinely communicating goals and expectations is important, managers are useful but only if they’re run well, more junior people and people from groups that are not overrepresented are less likely to be comfortable speaking up in meetings).

Key to this discussion, though, is the important of one-on-one meetings on retention. Managers who have one-on-ones with their team members do a significantly better job of retaining their staff.

Code that Doesn’t Rot - Maxime Chevalier-Boisvert

Chevalier-Boisvert points out the problem of “standing on the shoulders of giants” when it comes to writing code:

How much time do we collectively waste, every year, fixing bugs due to broken dependencies? How many millions of hours of productivity are lost every single day? How much time do we spend rewriting software that worked just fine before it was broken?

Back at the start of the 90s when I was in undergrad (yes, yes, I know) we were taught to write code to be “modular and reusable”. At the time, taking advantage of reusability basically never happened because sharing and discovering code was so hard. Here in the 20s, reusing shared modular code is absolutely routine, and — well, it turns out to be a bit of a mixed bag!

Chevalier-Boisvert gives good advice about trying to reduce unnecessary breakage: pinning dependencies; minimal software design (a la “do one thing well”); and VMs of various sorts with minimal APIs and requirements.

This is all good advice, and reducing dependency on unnecessary APIs and libraries can increase the productivity of downstream users. I’m wary of recommending this advice at the early stage of research software development, though, for a couple of reasons.

First, focussing solely on productivity: reducing use of dependencies can reduce the productivity of the developer, too. And since “Early stage” research software typically ends up having very few downstream users, trading developer productivity for user productivity can be a bad trade initially.

More controversially: higher productivity is good, and I’m in favour of it, but mere efficiency isn’t the most important reason for sharing research software. Being able to immediately run someone else’s code is awesome, but the thing that makes it science is being able to see and understand and reimplement the methods. That means making code available, sure, but also extremely clearly written documentation and methods sections (e.g. “Quantifying Independently Reproducible Machine Learning” in #12). So I’m skeptical of anything that slows down the development and open-source sharing of research software prototypes, even good things like spending time to make it robust.

As a piece of research software starts to inch up the technology readiness ladder and become a tool that people (even you!) start using, then the productivity of users weighs more heavily, and tradeoffs start changing. At that stage of development Chevalier-Boisvert’s advice becomes extremely important! It’s just worth being clear at what stage of development each product is.

startr - A template for data journalism projects in R - Tom Cardoso & Michael Pereira, Globe and Mail

There’s nothing startling in here, but I just continue to be amazed that the once-niche field technical computing and computational data analysis is now a field where newspapers post their open-source tools for template data analysis project structures. The Associated Press also has one, as does the UK civil service.

I will say that if you’re looking to teach a data analysis class, this is a pretty good one to look at. There’s a bit of a tutorial on a good data analysis workflow (raw data is immutable, write in pipelines, use tidy verse tools) and a number of small but useful utility functions.

After lying low, SSH botnet mushrooms and is harder than ever to take down - Dan Goodin, Ars Technica

A nice if somewhat discouraging overview of FritzFrog, an SSH botnet that’s unusually stealthy - it’s peer-to-peer (no easily spotted traffic to a central CnC server), there are 20 recent versions of the binary, is apparently smart enough to avoid infecting low-end systems liek Raspberry Pis, and payloads stay in memory and never land on disk. It’s not new, and has been around for two years, but has exploded in the past couple of months.

It listens on port 1234, scans constantly for open ports 22 and 2222, and proxies requests to local ports 9050, so it’s possible to detect based on network traffic. And, inevitably, some infected nodes start crypto mining, which at least is easy to spot from weird CPU + network usage. There’s a longer post here by Akamai, with a simple detection script.

An optimization story of calculating a absorption spectra. Would be very curious to see how using numba and/or JAX improved the Python implementation, as for instance here with numba.

Spin up a Galaxy instance for genomic data workflows on Azure.

Firefox - like, firefox the browser - had an outage in January. Here’s a nice retrospective, and an example of how to communicate with users after things have gone badly wrong.

I can not recommend this highly enough - is your inbox too full? Just archive it all. Add an “inbox_2021” label if it’ll make you feel better. It’ll still be there and searchable and responses will still show up in your inbox.

Nice tutorial for some intermediate git (rebase, amend, log) specifically in the very concrete context of contributing to a project via github/gitlab.

Caching is hard. A decade of major cache incidents at Twitter.

Database performance is also sometimes hard. Debugging a suddenly appearing performance problem with a Postgres query.

Selecting the most recent record in Postgres - group by vs lateral join vs timescale DB vs index scan vs triggers. Also, the guts of how postgres stores rows.

Writing as idempotent as possible bash scripts.

A comparison of six ways to package Python software.

And that’s it for another week. Let me know what you thought, or if you have anything you’d like to share about the newsletter or management. Just email me or reply to this newsletter if you get it in your inbox.

Have a great weekend, and good luck in the coming week with your research computing team,

Jonathan

Research computing - the intertwined streams of software development, systems, data management and analysis - is much more than technology. It’s teams, it’s communities, it’s product management - it’s people. It’s also one of the most important ways we can be supporting science, scholarship, and R&D today.

So research computing teams are too important to research to be managed poorly. But no one teaches us how to be effective managers and leaders in academia. We have an advantage, though - working in research collaborations have taught us the advanced management skills, but not the basics.

This newsletter focusses on providing new and experienced research computing and data managers the tools they need to be good managers without the stress, and to help their teams achieve great results and grow their careers.