Hi!

I wanted to talk a little bit more about Research Computing and Data (RCD), how it connects to other work, and how that informs how I think about when RCD work is and isn’t a research output.

First, I want to make a claim that most readers here would likely agree with, but may not yet be universally accepted elsewhere: RCD is a discipline in and of itself. It is a body of knowledge and practice, with full time practitioners, conferences, knowledge creation, sharing, and — increasingly — degree programs.

In fact, I’d make the argument that RCD been one of the most productive and influential academic disciplines of the last several decades. And an academic discipline it is - I don’t think anyone would doubt that the development of the FFT, or finite element methods, or new methods for processing next generation sequencing data or supporting digital humanities work, are real and significant research and intellectual accomplishments.

Research Computing and Data is a bit unusual in that it’s exclusively an applied discipline. There’s no real “pure” or “basic” RCD research work. Such work would fall into the fields of computer science (which is arguably a discipline that is itself a child of RCD) or applied mathematics or maybe electrical engineering (which are parents).

Instead, RCD work is always by its nature applied to some other area. And while being an applied-only field is a bit unusual, RCD isn’t completely alone in this. Engineering or even Statistics are overwhelmingly applied fields, but few would dismiss either of them as not being real fields of human endeavour, with real research outputs.

So let’s take it as given that RCD is a real discipline. I’d claim that the nature of disciplines is that they have an R&D practice. They have a spectrum of activities — all valuable! — which range from research on one end, to product development at the other. Crucially, there’s a point - maybe ill-defined, but it exists - at which the work stops being research itself and is now product development, just as is true for chemists, or materials scientists, or economists, or those in other fields. In those cases, the work stops being the creation of new knowledge in their fields, knowledge consumed principally by fellow experts in that field, and starts being about embodying that knowledge into something others can use. That embodying work is still work that requires expertise, it’s still work that builds on the history of work in the practitioners field, but it’s development of a product for use by others that needn’t be experts in that field.

Let’s say a materials scientist is doing some work that looks like it might lead to a new kind of sensor, that could be used in new kinds of lab equipment. Initial discovery work showing that it could work as a proof of concept, or even as a prototype, probably involves a lot of research work. The primary output is new knowledge about materials science, knowledge published in journals and that other materials scientists can build on.

Let’s then say the team then contributes to work to commercialize that knowledge, to actually build the sensors that can be incorporated into new lab equipment. At that point the work stops being principally about producing new materials science knowledge and starts being about creating a new product that relies on, that contains, that embodies, that knowledge. There will be lots of careful, methodical, expert-level work done building packaging that doesn’t compromise the properties that make the material a good sensor, of building sensitive and reliable ways of measuring output from the packaged sensor. That’s excellent and important work, and will be used in lab equipment for research, but relies much more heavily now on existing best practices built up from previous product-building work. It need not and likely will not lead to the development of new materials science knowledge. It doesn’t generate materials science research outputs. That’s true even if it will be used to help support research in other fields.

This research-to-development journey doesn’t have to be strictly linear! It could be that in building the packaging new materials science knowledge is required. And to develop the next version of the sensor, it’s certainly possible that new materials science knowledge ends up being developed, generating materials science research outputs. But it’s also possible that it doesn’t, and that the work done is purely product work, developing a product rather than new materials science knowledge.

I think about research computing and data work, the work of research computing teams, the same way. Because RCD is always necessarily applied, I sometimes find it useful to think of it not as a one-dimensional research to development spectrum, but in a two-dimensional space - considering how mature the RCD work itself is, and how mature the problem is it’s being applied to are.

In the case of creating a new sensor, the problem is evolving and becoming clearer along with the product itself - the path lies more or less along the diagonal. That’s also how I feel about much of bioinformatics, a field that has grown in parallel with — both being driven by and in turn driving — developments in high-throughput molecular biology data collection. Along that diagnal there is a very exploratory phase, where you’re not even sure what questions make sense to ask, through to turning things into prototypes, through to delivering a mature product. Along that diagonal (which again needn’t be followed strictly linearly) work changes from producing mostly new RCD knowledge to packaging that knowledge into a product that non-RCD experts can use.

But there’s alternatives to developing tools that grow in maturity with the field. In the top-right corner, with new RCD solutions but mature problems, new methods can be applied to extremely mature fields — a new numerical method for fluid dynamics, for instance. Novel methods, in any field, are more or less always recognized as research outputs. In these cases “product development” is much simpler - going from that proof of concept to something in production is likely something that can happen quite quickly, as the needs of users are very well understood, and there’s probably existing tooling you can build on to deliver the new method into the hands of users really quickly. On the other hand you could build new frameworks for existing methods; that’s useful, but is less likely to be a research output, building more on software development best practices than generating new RCD knowledge.

In other corner, you have mature RCD outputs being applied to new problems. This is the work of translation; of realizing an existing method can be applied to answer new questions. That work can quite possibly generate both a new product and new RCD knowledge.

I won’t claim that this is The Answer to RCD as a research output, but it’s a robust, self-consistent and well-motivated take. I think we haven’t thought about RCD in terms of R&D mainly because up to this point, we’ve mainly been thinking of RCD solely in terms of research software development. Since we want research software by and large to be open source, a commercialization approach seems weird; and as long as grant funding rates were really good, it was easier just to treat RCD products as research outputs and get them funded and recognized following that approach.

But this is growing untenable, for a number of reasons:

I don’t know what the solution to any of the above is. But thinking more clearly about the purpose of our work and what success looks like, and RCD’s place as a discipline, is more likely to get us there than just continuing to hope that RCD work can be funded in the same way as doing experiments or theoretical analyses.

Sorry, that was long! Now on to the roundup.

Onboarding Can Make or Break a New Hire’s Experience - Sinazo Sibisi and Gys Kappers

I’m obviously thinking a lot about onboarding lately!

When we do hire, we often put a lot of work and effort into actually finding and hiring someone, and then the work kind of … stops. There’s not a lot of effort put into the “on ramp” to the job, getting people geared up and ready to succeed in their first three months or so. That makes the new hires unhappy - you’ve presumably made a point of hiring someone who is a high-achiever and wants to get stuff done - and it makes the other team members unhappy as it takes a long time for the new hire to come up to speed and pull their weight.

This situation is particularly dire in research computing, where we don’t get to hire very often and so any onboarding plan and materials we might have are probably way out of date. One of the reasons I really like hiring student interns year around is that it presents a huge opportunity (if taken, which I didn’t always do!) to get the hiring/onboarding/offboarding processes running really smoothly, and to improve it over time.

Sibisi and Kappers walk through their recommendations for improving onboarding. Like so much in managing, it’s not rocket science and the recommendations aren’t huge flashes of insight - it’s paying attention to the details and doing the work

Mentoring Conversations: How to Be Remarkably Helpful with Limited Time - Karin Hurt, Let’s Grow Leaders

How to improve your listening skills? Here are five tips. - Laurie Brown

Honestly I’m pretty down on mentoring in this newsletter, not because it’s bad but because advice is often so cheaply given compared to (say) actively sponsoring a team member for new opportunities.

But.

If you’re deeply thinking about what your mentee wants and ask a lot of questions, particular questioning their assumptions and using something of a more coaching approach to help them find their own answers, it can be really valuable. Hurt here describes a mentoring conversation that changed her career path.

Relatedly, Brown reminds us that listening well takes a lot of effort and practice; her five steps for listening (in mentoring or other conversations) are:

Reverse Interviewing Your Future Manager and Team - Gergely Orosz

There’s no perfect jobs, but there are bad jobs, and there are overall good jobs which nonetheless are a very bad match to what you personally prefer and want to be doing every day.

Once you get an offer you can start reverse-interviewing in earnest. I don’t mean the “what does success look like in this role” kind of question you ask in the last 5 minutes of a 60 minute interview slot, I mean really digging deep to figure out what working in the job would actually be like. Especially if you have a couple of offers (and todays environment is very conducive to getting multiple offers), the information uncovered here can help guide you to a choice you’ll be happy with for a few years.

Besides any specific questions that you have after thinking about the role and the organization - anything which seems odd or surprising to you - Orosz and some of his colleagues contribute some pretty good general purpose questions for the hiring manager but also senior peers you’d be working with:

Even if the answers only solidify your decision to join the new company, they will be useful for giving you a head start, knowing better what to expect in your first months.

National Science Foundation Announces ACCESS Awards - Dina Meek, NCSA

ACCESS, the follow-on to XSEDE, is starting to take shape as $52 million over five years for (as I understand it) personnel and models for service delivery are awarded by NSF.

In NSFs call there were four separate tracks, for handling allocation services, for handling user services, for operations and integration between the different systems, and for monitoring and measurement services. (I have to admit, as an outsider, it’s not obvious to me why the last two would be separate). Then there’s an overall coronation office, which will be run out of NCSA.

With the awards just announced, details are sketchy - XSEDE will be active through August, so ACCESS will have several months to ramp up, and presumably we’ll learn more over the summer. But even with the press-release-level information, I’m fascinated by the most user-facing two of these: RAMPS (out of PSC) for allocation, and MATCH for user support.

RAMPS looks like there are a number of useful ideas that will come into play:

Do we have any readers who know more about the details of MATCH or RAMPS (or the other awardees) who are comfortable sharing some information?

As in-person conferences recommence, regional conferences of running scientific core facilities (like this one for the mid-atlantic states in the US) are beginning to start back up. The managers and staff of these core facilities have a lot of expertise in sustainably providing service offerings to research, and lots of experience in service development, service lifecycles, and business case modelling. I’m not sure I’d recommend making a trip just to attend one, but if there’s one at or near your institution it could be a useful way to network with other leaders and managers facing similar challenges as RCD teams, in a different context.

Storing 64-bit unsigned integers in SQLite databases, for fun and profit - C. Titus Brown

A blog post about research software development that touches on the challenges of working on a giant pull request, using SQLite in a research software code, and discussion of tradeoffs in different approaches is, as longtime friend of the newsletter Brown must know by now, too much for me to resist including here.

In this article, Brown describes moving sourmash away from the custom-built inverted index and sequence bloom tree into using SQLite as a searchable backing store connecting kmer hashes to the sequences containing the kmers. These get quite large (4.6 billion hashes), so efficient approahes are important; but efficiency means a few things here, ideally it would be low disk usage and fast and low memory usage, and of the three likely at least one will have to give. Hashes are an interesting problem for this, too, because since they’re hashes they don’t support (say) range searches; locality doesn’t mean anything in the hashed space.

Longtime - or heck even recent! - readers will know that I think embedded databases are criminally underused in research software, and Brown too really likes SQLite in particular, so he wanted to see if SQLite could be used here. That’s not trivial because SQLite, while great, has actually pretty weak support for types, and in particular doesn’t support 64-bit unsigned ints at all. The first appraoch didn’t go well! But by understanding the structure of the data - in partiuclar since order didn’t matter with the hashes, he could type pun unsigned ints into signed ints as long as it was done consistently - he got very good results, consistent with the tradeoffs that made sense for the sourmash product (allowing more diskspace use for the index if it makes lookups faster while keeping memory useage down). There’s also some solid PRAGMA choies described for read-only workloads like this one.

It’s a good article to read if you’re thinking of taking advantage of sqlite or other embedded databases for data lookups as opposed to “rolling your own”.

EULAs Aren’t Inherently Evil - Kyle E. Mitchell

Mitchell is a tech lawyer who the newsletter has linked to in discussions of open source development in the past (such as #83 on contributor license agreements). Here he makes the case that non-open-source software isn’t (pace, say, the FSF) inherently evil.

In research computing there’s an overwhelming case for needing source to be available for simulation and data analysis methods, but not all research computing software falls into those categories, and such availability needn’t only be through the traditional open source licenses.

Until we’ve figured out a way to make the development of RCD software products sustainable through traditional funding sources in the long term, we can’t completely rule out supplementary funding models for product development like hosted software-as-a-service, selling support, or just flat out charging for software. I’m watching infrastructure projects like nextflow with interest, with a sort of “freemium” model of an open source community edition core and then Sequera Labs charging for hosting and support (and clinical labs actually prefer to pay for support for key tools). To make that work, we may have to consider a broader range of licensing models. I don’t love the idea either.

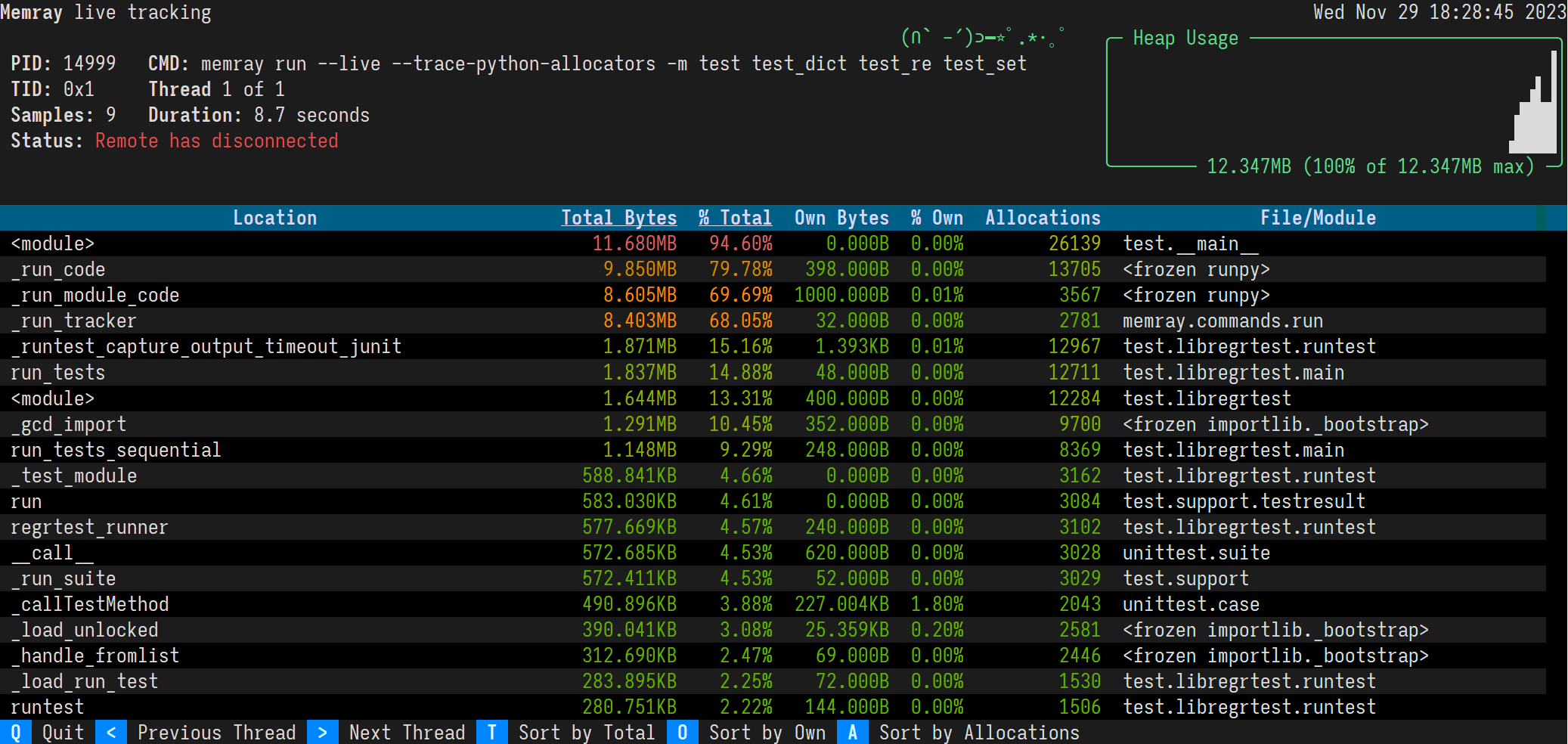

Bloomberg has open-sourced Memray, really useful looking python memory profiling tool that runs standaloneor can be queried via APIs.

Securely pushing to GitHub from a JupyterHub with gh-scoped-creds - Yuvi Panda

Potentially useful well beyond Jupyter, gh-scoped-creds is a github app which issues time-limited, repository-scoped credentials for your GitHub account that can be used to push changes in JupyterHub or on other shared systems where you might want to automate some github actions but don’t want your credentials lying around.

Push ML methods as far into the database as possible with the open-source MindsDB - I think this is an under-appreciated approach, and for some use cases will be a significant win over trying to do something clever and resource intensive with distributed systems.

An emerging light-weight stripped down alternative to elasticsearch - sonic. Cool looking, but as ever, mind how you spend those innovation tokens.

CVE-2022-21449: Psychic Signatures in Java - Neil Madden, ForgeRock

More Java security issues, where new (Java 15+) updated and improved(!!) code for handling ECDSA signatures. Except it meant that such signatures could be trivially bypassed by the sender, with any signature being “valid” if one parameter is set to zero. That isn’t great if it’s being used for e.g. JWT validation. The bug’s been there since the start of 2020, and known since at least Nov 2021, and fixes are just being rolled out now.

Luckily I doubt most of our systems are running such up to date version of Java - i.e. Keycloak relies on Java 8 or 11.

New Ubuntu LTS just dropped. Some notable updates from my point of view is continuing mainstreaming of deep Arm support, OpenSSL moving to 3.0 which disables a lot of legacy algorithms (yay!), a move to nftables, and a major OpenLDAP update.

In the new job, I’ve been thinking about slurm installations a lot more than before, when I took it as a given. So these are new-to-me resources that might not be new to you - a docker-compose slurm “cluster” SchedMD uses for testing and training and one University of Buffalo uses that also have e.g. OpenOnDemand, OpenXDMod, and ColdFront.

A Case For Intra-rack Resource Disaggregation in HPC - George Michelogiannakis et al, ACM Transactions on Architecture and Code Optimization

Disaggregation of systems has been coming up more and more often in the roundup (just last week in #118 as a motivation for Aquila, when talking about two testbed systems in Texas a couple weeks earlier in #116, and as a topic of more than one conference listed in January’s #105).

This paper by Michelogiannakis et al quantifies the potential usefulness on the HPC side, taking a look at real-world data from NSERC’s top-20 cpu and knights-landing Cori system, augmented with profiling data from elsewhere on GPU-heavy ML jobs. (The authors go into quite a bit of detail in the paper - it’s worth reading even if you’re just interested in workload characterization of Cori. )

Anyone who’s been involved in helping researchers take advantage of large computing systems will be familiar with the basic motivating idea here. While you can often (sometimes with a lot of work!) get a simulation or data analysis code to take full advantage of a node’s cores, or its memory, or its memory bandwidth, or its network bandwidth, or its accelerators, or its local storage, pegging the needle on two or more of those resources at once is harder. Taking full advantage of all of them at once basically never happens — and if it did, it would mean the code would almost certainly have to be adjusted to be run effectively on another system that had a different mix of those resources. (This, by the way, is one why a single “utilization” number for a cluster with a mixed workload is a useless metric even if you’re inclined to believe that utilization of a scientific instrument is the sort of thing which should be a metric).

Since all of our systems are running a mix of jobs with a different profile for taking advantage of those resources, there’s no real “one-size-fits-all” best node size. What if you could “mix and match” within a rack (say), taking some unused cores or memory or GPU from one node and distributing them virtually to another node where they could be used?

In this paper, the authors look at how Cori is actually used, and find that if there were perfectly efficient ways of distributing the disaggregated resources at the rack level, they could cut back on memory or network bandwidth by 5 to 69% per rack and still satisfy worst-case average needs within a rack for their jobs. That would would free up resources to be used elsewhere - maybe in more racks, maybe by hiring more staff - and also can be used to give rough and ready potential benefits to be weighed against performance and price costs of emerging disaggregation technologies.

“Smarter” NICs for faster molecular dynamics: a case study - S. Karamati et al, arXiv:2204.05959

(I’ll note before starting that paper describes work using NVIDIA SmartNICs/DPUs. The kinds of things the authors here are trying to do to take advantage of smarter programmable network cards apply more generally to this class of device, though, and the results here are sort of mixed and took a lot of work - it’s far from an advert for these cards! So I’m pretty comfortable including this article in the roundup.)

Here Karamati et al try various approaches to improve the performance of a simple application using SmartNICs. The application they work with is MiniMD, a simple sample application for molecular dynamics demonstrating patterns broadly similar to the much more complex and powerful LAMMPS code. MiniMD’s main purpose is to be a testbed for playing with various parallelization and programming approaches.

MiniMD is an interesting choice from among the Mantevo mini-codes because it isn’t principally communications bound (from the github repo: “Any reasonable parallel computer should be able to achieve excellent scaled speedup (weak scaling)”). It also has pretty a pretty serial per-node compute-and-then-communicate structure which makes overlapping communication and computation tricky. Finally, there’s not a lot of collective operations (except for an all gather) in MiniMD. So it’s not obvious that putting more smarts in the network card is a route to improving performance of this code.

Sure enough, they don’t get any speedup from the code as it is. On the other hand, by restructuring the code to separate out ‘maintenance’ work (updating neighbour lists) from the main computation loops, thus increasing the task parallelism and giving the Arm cores in the NIC something useful to do in parallel as a coprocessor, they improve performance by up to 20% (while increasing power consumption only 6-13% because of the lower power consumption of the Arm cores now enlisted in the work).

The authors make the comparison to other kinds of accelerators - taking advantage of them may require code rearchitecture. I’d add that once that is done, other possibilities arise - for instance, I’d be curious to see how exploiting this newly-found task parallelism might work even on purely CPU systems.

This is pretty cool - Docker now has an experimental docker sbom which will attempt to produce a software build of materials for a container image.

The singularity project reports on twitter that, thanks to work on unprivileged cgroups, Singularity CE 3.10 will let you do things like assign fractions of CPUs to containers. I know at least one group that’s playing with having jobs, or even login node sessions be encapsulated in a singularity image - this could be useful for that work, or even just as a template for using unprivileged cgroups in other contexts.

The fascinating history of Lotus Improv, 1991s most innovative take on spreadsheets, with an unquestionably better underlying take on data and which equally unquestionably failed completely. (Check out the incredibly late 80s/early 90s video!)

We’re going to see some extremely cool things done with this - The General Index, a downloadable n-gram index (n ranging from 1-5) of 107,233,728 (so far) academic journal articles.

Todo lists in the editor - must we? Who cares what those weirdos do with their “org mode”? Fine, ok, whatever. Here’s Vim Tada, a todo list for vim.

Learn about assembly on the ZX spectrum.

A very complete list of terminal tricks for Mac, aimed at those new to the terminal but including some Mac specific things I hadn’t heard of.

Parsing and validating dates in Awk. Look, I’m not going to judge, I’ve done unspeakable things with sed. Think of it as harm reduction, keeping the kids from getting into perl.

Pre-commit hooks for avoiding accidentally committing secrets to your git repos - ripsecrets.

A student license for OpenVMS on windows.

A lovely interactive visual tutorial on different approaches to rotations in 3D, and maybe the only quaternion explanation you’ll ever see featuring an adorable cartoon cow.

A promising-looking logging SSH gateway for bastion hosts - warpgate.

rqlite is a distributed relational database built atop of of sqlite. It stood up to Jepsen-style testing which is no small thing.

I’m not sure that implementing a message queue in the shell is a good idea, but it makes for a good tutorial introduction to the topic.

I wouldn’t say that compiling rust software for Windows95 is a bad idea, exactly, but I’m not sure why you’d want to.

On the other hand I’m pretty sure using dropbox as a backing store for a git repository is a bad idea, but I guess if you know the risks?

I’m absolutely certain that managing code repos from within your database is a terrible idea.

For the love of god do not implement your own linear algebra library in C.

And that’s it for another week. Let me know what you thought, or if you have anything you’d like to share about the newsletter or management. Just email me or reply to this newsletter if you get it in your inbox.

Have a great weekend, and good luck in the coming week with your research computing team,

Jonathan

Research computing - the intertwined streams of software development, systems, data management and analysis - is much more than technology. It’s teams, it’s communities, it’s product management - it’s people. It’s also one of the most important ways we can be supporting science, scholarship, and R&D today.

So research computing teams are too important to research to be managed poorly. But no one teaches us how to be effective managers and leaders in academia. We have an advantage, though - working in research collaborations have taught us the advanced management skills, but not the basics.

This newsletter focusses on providing new and experienced research computing and data managers the tools they need to be good managers without the stress, and to help their teams achieve great results and grow their careers.