Long time reader Adam DeConinck wrote in answering a question about Firecracker, a light-weight VM which is used for hosting tools like (as in last issue) CI/CD pipelines:

I love Firecracker, but so far there’s no support for PCIe pass through (eg GPUs, NICs, etc). Which I find really unfortunate […] because research computing in general is making heavy use of such devices, wherever they get them. I’d love to see a micro-VM approach in HPC at some point. Or really anything that can provide a better multi-tenancy story for shared research computing facilities in an increasingly security-conscious world. And as some Kubernetes devs have reminded me lately, the kernel (and containerization) are not a security barrier. […] Selfishly, I just want a VM platform that’s as easy to use in HPC as Singularity or Enroot.

Ah that’s interesting — thanks!

The current top question on the polly list (which has been pretty quiet - cough cough) is on writing a job advertisement. This will probably take more than one issue to address. It’s a absolutely key question (and I’m going to write out “job advertisement” pretty consistently, because too often we forget that’s exactly what it is — a document whose purpose is to be advertise our job and attract potential candidates), but first I want to address the hiring wrong-way-round approach I see too often in our community (and, to be fair, in many many others).

A very common meta-mistake a lot of teams make when hiring is to consider it as a sequence of discrete, loosely related checkboxes, to be completed in the order that they’re needed. Write up a list of features we expect a new candidate to have; post it some places; recruit some candidates; figure out some interview questions; choose someone to give an offer to. Then once someone’s hired there’s a second series of checkboxes, which must be completed in order: onboarding; figuring out what they should work on; evaluating and managing their performance.

I call this a meta-mistake because this mental model then causes a bunch of mis-steps and needless hassle, for the manager, the team, and the candidates.

The truth is that everything described above is best worked on as a single coherent process. The process begins with a (funded) but still vague need on the team, and ends with a successful, integrated, new team member killing it after their first six months. Adopting that mental model and taking it seriously means front-loading some of the work, but enormously increases the chances of success. Not only are will you end with a team member who doing well, but you’ll have had a better candidate pool, and the non-hired candidates who might be (or know!) a good match for future opportunities, will think well of the professionalism of the process.

And like most processes, when planning for how it will unfold, it’s best to begin with the end in mind.

Let me begin with a bit of unsolicited advice for your own career development. When you’re next interviewing for a job, and it’s your turn to quiz the hiring manager, ask the following common question: “What does success look like in this job? What would make you say, after six months, ‘This was a good hire, this really worked out well’?” This is a common, almost banal, question, but one where the answer can be very helpful for you in evaluating the job. So is a lack of an answer. If they do not have a coherent and confident response, that’s a red flag. They do not have a plan to make sure a new hire succeeds in their job; they can’t, because they’re not even sure what outcome they’re aiming for.

From the hiring team’s point of view, the whole purpose of any hiring process can be summed up by them being able to honestly say to themselves “This was a good hire, this really worked out well.” From a candidate’s point of view, the purpose is to end up in a job that can put their skeills to good use, and to succeed at a job they enjoy. A hiring team able to clearly articulate that successful end state makes both sides more likely to get what they want.

So it’s disappointing how many times I’ve lobbed this softball of a question at hiring teams (as an advisor or as a job candidate) and watched people scramble and duck for cover as they search for something to say in response.

Lou Adler relentlessly popularized the idea of “performance-based hiring,” focussing first on what the successful candidate will actually do several months in (“performance profiles”) rather than looking for people who have a laundry list of features the hiring manager thinks they should have. His book has some really strong sections. But it’s not a new idea. There have always been managers who thought of hiring, and communicated their open positions, using precisely this approach.

There are some completely general advantages of starting planning of hiring process from the final state, success three-to-six months post hire:

There are particular advantages for research computing and data teams, too. Say you’re an RCD team looking for a new e.g. data scientist or research computing facilitator or software developer. Often these teams have two or more quite different areas of domain expertise — say quantum science or digital humanities — that they want to grow in, but they’re not fussed by which specialty they hire for first (zero points for guessing whether I think that ambivalence is a good idea, but it’s a situation some teams are stuck with). Clearly describing a successful research facilitator on your team, supporting research in their specialty, is a much more fruitful starting place than trying to come up with a Venn diagram of previous experience and skills spanned by the two areas. Especially when this might be your first digital humanities hire and the team would struggle to come up with a skill list to start with!

With a clear view of what success looks like after four months, the team can start planning a road to get there for a new hire: what would be expected after two months; after one month; after two weeks; after one week. Hashing out and creating some agreement about that successful end state with a team is a very useful discussion to have.

These should be quite detailed, and when you agree on them they can be incorporated into a job advertisement. Here’s a couple I’ve written for two different sorts of jobs (note the longer timescale in the leadership position):

Delivery Manager:

A successful hire in this role would, by 3 months:

By 6 months:

And by 12 months:

Network operations/observability Senior IC:

In your first month you will:

In your second month, you’ll:

In your third month, you’ll:

Once an early progress plan firms up, you can continue working backwards: begin the process of creating an onboarding plan to help them get there, some prerequisites for what a person would need to have and be able to learn to get there, and defining evaluation criteria. I have an early draft of a worksheet for that planning here (letter, A4). I’ll come back to that process later. Next issue I’ll come back to this, assuming that work’s been done, and address the actual question, how to put that information into a job advertisement.

Until then, on to the roundup!

Good Managers Matter a Lot! (Twitter Thread) - Ethan Mollick

What you do matters, and there’s a reason that my priority right now is to focus on front-line managers. Here’s a twitter thread by Mollick, a professor in the Wharton School at Penn State, highlighting some research results. The ones that stood out to me because they were more about front-line managers:

The experts in our teams doing the hands-on work deserve to be supported, have opportunities to grow, and have good working relationships with their peers and their mangers. The research we support deserves that 22% or 30% boost in productivity that comes from a well-functioning team. (Honestly, I’ve been in dysfunctional teams and healthy ones, and 22-30% seems small). And I’m tired of a research ecosystem which doesn’t value the value of managers, the effort they put in, and the stress they’re put under by not being given support.

(And, because I’ll get questions otherwise: the rate of people leaving a team shouldn’t be zero, change is good and healthy, for the individuals and for the team! But good team members should leave because they have fantastic new opportunities that will grow them in new ways, not because they feel under-supported and trapped with no input or career path).

(Somewhat relatedly, also via Mollick - toxic workers cost a team more than twice as much as hiring a superstar benefits a team)

Don’t Shy Away or Risk Cowardly Management - Aviv Ben-Yosef

Let’s start with a simple test for how you can self-assess whether you are being too shy. If you finish most workdays with a weighing down feeling about an issue that you have not spoken to the relevant person about.

I’d prefer the word “timid” to “shy” above, but Ben-Yosef is exactly right. Tech and academia have a lot of the same interpersonal issues:

I’m not a big fan of stereotypes, but there’s no denying that a lot of leaders in tech are former engineers–a group no one would claim is known for being overly talkative. Providing frank feedback about technical matters is one thing, but saying what’s really on your mind, especially when it comes to personal matters, is something that you might find quite a bit harder.

Not giving a team member critical feedback is a small act of cowardice. An understandable one — we’ve all been there — but still. Your team members deserve to know when they’re not meeting expectations. You’d want to know from your boss! You’d be mortified to hear that they had been grumbling to themselves about something while not telling you about it. Give timely feedback: respectfully, kindly, but firmly. Feedback is a gift.

Realistic engineering hiring assessments - Tapioca

Explicitly testing for needed skills is an important tool to have in the toolbox as you’re constructing a hiring process. For technical staff, that would be some kind of technical test - it could be having people walk through code, review code or architectural choices, or some kind of take-home assignment.

There are real downsides to take-homes! Many potentially excellent candidates don’t have 2-3 hours per job application to spend in their off time doing work for a job offer that might never come. For technical staff who generally don’t need to “perform on command” in front of an audience, there are also real downsides to doing it live in front of an audience (many people, especially those in groups that are not overrepresented in our fields, demonstrate less confidence in those situations and so are graded much worse), and real downsides to having people demonstrate a code/architecture portfolio (lots of people don’t code in their spare time and are not at liberty to show their work from previous jobs).

Increasingly I’m coming down on the side of offering candidates a choice between options, and having one of those options be a short take home (replacing, rather than in addition to, the equivalent number of hours of interview process). Tapioca (which, to be clear, sells a platform for running take home exercises at significant scale) has a curated list of ranked take home problems, if you need inspiration. To my mind, many of these are too long to be justified (although they might be excellent discussion problems along the lines of “think about how you might do this and the tradeoffs of different approaches, and we’ll discuss it in the interview”). But they cover a wide range of skills and approaches.

Being-Doing Balance over Work-Life Balance - Jean Hsu

I’m very cautious about sharing traditional productivity stuff here, because (a) efficiently doing the wrong things doesn’t help anyone, and (b) lots of “productivity hacks” work great for some people while not working for most.

But also there’s a bit of a reverence for being productive (or worse) being busy in our line of work that can be deeply unhealthy, but is also pretty seductive for those of us who get into this work because we’re high achievers.

Hsu’s distinction here I think is right; “Being-Doing” is a more useful mental model than “Work-Life”. If you’re spending your days depleted because you feel the need to constantly be accomplishing things at work and then you spend an equal amount of time just as driven to accomplish things at home, that’s not great, even though work and life are balanced. We need to find some time to just be, without any accomplishment at stake. That can come from coffee with workmates, family time, honing a craft for its own sake, hobbies, and any of a number of other things that work for us.

SQLite: Past, Present, and Future (PDF) - Gaffney et al, VLDB ’22

Business school students learn a lot of strategy through case studies, a form of education we generally don’t get in STEM fields. So I like to read (and include here) case studies of products relevant to our line of work. Reading them helps us understand a successful product teams thinking, what they’ve optimized for and why, and how they make their decisions.

(Someday I’d very much like to assemble a compendium of case studies of strategy for various research computing and data teams. Not finished strategic planning documents, which aren’t useful outside of the team’s immediate community, but how and why the choices that informed that document were made, which could be extremely instructive quite widely.)

This is a nice history of SQLite, the choices it made, and what it chose to optimize for. There’s a long, unflinching comparison to DuckDB, which absolutely smokes SQLite for analytic workloads (and in turn performs vastly worse on transactional workloads), and a discussion of what the team would and wouldn’t be willing to compromise on to improve SQLite’s analytics performance.

Another article on how hard it is to find postdocs this year, this time in Nature.

I sympathize with the PIs in this situation, many of whom are junior faculty struggling to establish themselves. But I’m not sorry this is happening.

Every week researching the job board I see dozens of postdoctoral postings that should clearly be staff jobs. Instead they are precarious year-to-year positions with poor pay and worse benefits. That was sustainable as long as postdoctoral candidates were willing to sustain it in exchange for possible future faculty positions. That willingness has clearly changed. Time will tell if it has changed permanently.

About Scientific Code Review - Fred Hutch Data Science Lab

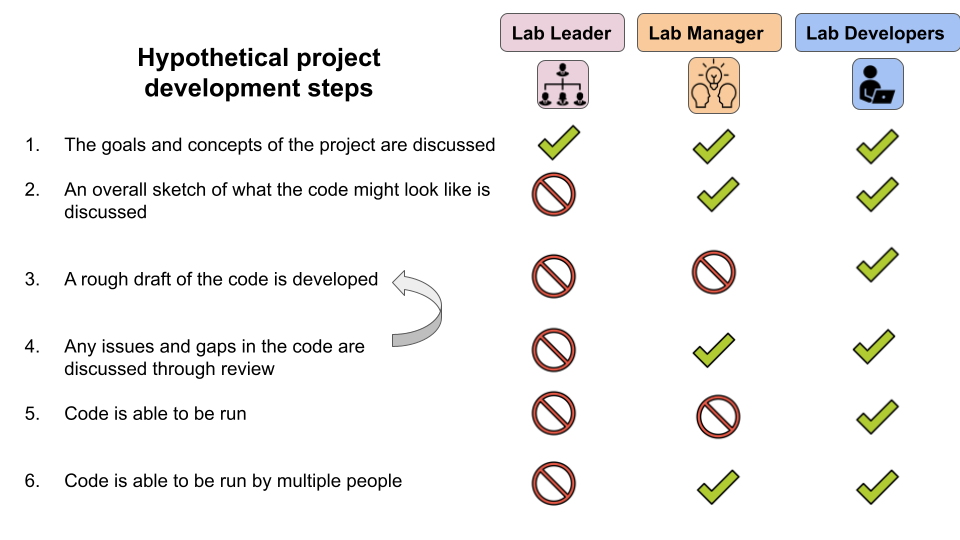

Here’s a good introductory overview of code review for science (and in particular data work) by the Fred Hutch Data science lab. It’s a great resource for teams getting started, whether a staff team or maybe a researchers group you’re working with. One thing I like this is that it breaks the various tasks up between roles - developers, lab managers/team leads, and lab leaders. Groups in different situations may have a slightly different assignment of tasks to roles, but it’s nice to see the roles clearly distinguished. Then there

Groups getting started in code review might also be interested in an upcoming (Oct 12) webinar hosted by the Exascale computing project entitled “Investing in code reviews for better research software”.

The Australian Research Data Commons is sponsoring an Australian science award recognizing research software! Let’s see other groups follow suit.

So! You want to search all the public metagenomes with a genome sequence! - C. Titus Brown

Brown talks about exciting work by Luiz Irber to enable similarity searches across metagenomes, extremely complex and large data objects hundreds to millions of times the size of a genome. This is an extremely useful scientific capability, but with their previous technologies it would take minutes per search.

Like the DuckDB vs SQLite comparison above, choosing the right database for the job makes a huge difference! Irber tried another implementation using RocksDB, an embedded key-value store rather than a tabular relational database, and search times dropped from minutes to seconds. This makes lots of new things possible - now the team is working on performing a sketch of local private genomic data in the browser (using webassembly, which you will know this publication is almost as big a fan of as embedded databases) and interactively query a web service.

New data types are changing research needs dramatically, and technologies previously not really useful for research computing are starting to play increasingly important roles. This is an extremely exciting time to be supporting this kind of work!

(Beating one of my drums for the umpteenth time - is this a software development project? A systems project, for the hosted service? A data management and analysis project? Like an increasingly large fraction of all impactful research computing and data efforts, it doesn’t fit into one silo or another - it’s combines the contents of two or more. While the categories may work ok as section headings for a weekly newsletter, dividing our community into research software development or research systems or research data is actively counterproductive).

Meta’s Velox Means Database Performance is Not Subject to Interpretation - Timothy Prickett Morgan, The Next Platform

Data lakes are increasingly important for data-intensive research computing teams in a way that seemed extremely unlikely even ten years ago. That means “federating” data across multiple data sources. Those doing that work may be interested in another VLDB paper Morgan summarizes, describing Velox which is a uniform high-performance (C++) query execution engine being tied into multiple data systems:

Velox is currently integrated or being integrated with more than a dozen data systems at Meta, including analytical query engines such as Presto and Spark, stream processing platforms, message buses and data warehouse ingestion infrastructure, machine learning systems for feature engineering and data preprocessing (PyTorch), and more.

Paving the way for a coordinated national infrastructure for sensitive data research - DARE UK

As research computing and data continues to expand beyond the basic research and the physical sciences, environments and methods for responsibly handling sensitive data in a trusted manner is becomign more important. Here’s a report of phase one of the UKRI “Data and Analytics Research Environments” (DARE) program, which taught to identify key challenges and needs. It offers concrete high-level recommendations on demonstrating trustworthiness, researcher accreditation and access, accreditation of the environments, data and discovery, federation of these environments, building capability and capacity, and providing funding and incentives.

Of particular note, under “Capability and Capacity”, the report emphasizes the need to focus on clear career pathways, better visibility and recognition of the technical roles, better salaries, and and excellence in training.

Unless you’ve been living under a rock this week (and honestly, these days who could blame you) you’ve heard of Stable Diffusion, a publicly released image model a la DALL-E from Hugging Face that you can download and run yourself. People are doing remarkable things with it, especially with the image-to-image functionality (where the prompt includes an image). Some are helping you create animations interpolating between two text prompts, others are explaining what diffusion models are, others still are creating searchable indices of some of the training set, or getting it to run on apple silicon.

Interesting - Sioyek is an open source PDF viewer specifically for academic and technical papers, with features like a table of contents for navigation and smart links to figures, tables, and references, even if the actual PDF file doesn’t provide those things.

A very promising-looking course for getting started on GCP for bioinformatics.

A really nice visual walk through of how pointer analysis works, and in particular how the open source cclyzer+ tool works with LLVMed code.

A short handbook on writing good research code, which might be a good resource for trainees you work with.

Apparently if you’re the maintainer for software that configures monitors, you end up with a collection of all the weird bugs monitors have (and blame you for).

Naming things is hard. Introducing USB4 2.0.

Maybe relatedly, this week I found out that cram was an interesting looking tool for writing command-line test suites; and cram (no relation) is an interesting looking dotfile manager.

Claris is renaming FileMaker Pro, causing computer enthusiasts my age everywhere to cry, “wait, FileMaker is still a thing?”

Continuing the old-person computing nostalgia theme, apparently people have finally come up with a use for the Commodore 64 (as opposed to the clearly superior TRS-80 Color Computer which just happens to be what I had) - turning it into a Theremin (with a nice explanation of how they work. Theremins, not C64s.)

And that’s it for another week. Let me know what you thought, or if you have anything you’d like to share about the newsletter or management. Just email me or reply to this newsletter if you get it in your inbox.

Have a great weekend, and good luck in the coming week with your research computing team,

Jonathan

Research computing - the intertwined streams of software development, systems, data management and analysis - is much more than technology. It’s teams, it’s communities, it’s product management - it’s people. It’s also one of the most important ways we can be supporting science, scholarship, and R&D today.

So research computing teams are too important to research to be managed poorly. But no one teaches us how to be effective managers and leaders in academia. We have an advantage, though - working in research collaborations have taught us the advanced management skills, but not the basics.

This newsletter focusses on providing new and experienced research computing and data managers the tools they need to be good managers without the stress, and to help their teams achieve great results and grow their careers.

This week’s new-listing highlights are in the email; the full listing of 214 jobs is, as ever, available on the job board.