A housekeeping item before we get started -

I’ve had the searchable archives for back issues for a while, but there’s a limit to what a simple text search can do. I’ve wanted to have previous articles and write-ups browsable by category for some time now. There’s two time-consuming parts to that - going back and curating the best-of evergreen articles (right now mostly from the roundup), and then figuring out how to make them available.

I’ve done a first pass at the first piece, and now have a VERY crude initial attempt at this - so far what I think it’s taught me is that I’ll need some sort of hierarchy to the tagging of articles, which I need to think a bit about. What would be useful to you in a categorized “best-of” list? What would you like to see? Drop me a note - hit reply or email me at jonathan@researchcomputingteams.org.

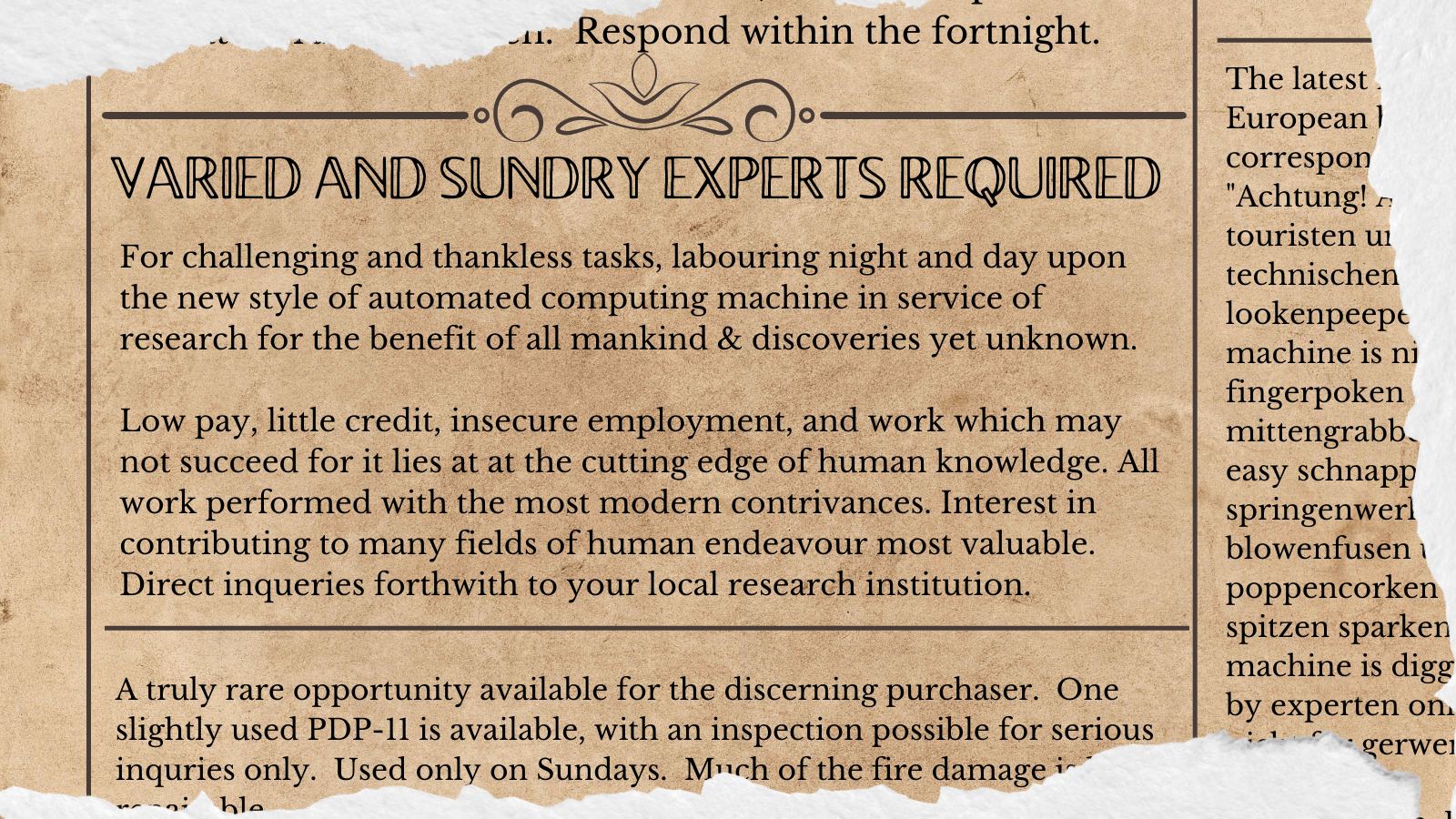

I want to continue the discussion about job advertisements. When we left off, we had a description of what the new hire would be doing and succeeding at after 4-6 months in the new job. That can and should be part of your job advertisement.

Let’s start with two seemingly-contradictory points.

First, your job advertisement is exactly that, an advertisement. It is an external document, not an internal one. Its one purpose for existing is to be a compelling description of your job to show to candidates who would be good matches for the job and who might be interested, and to induce them them to apply. It’s a sales landing page. But…

Second, we want to get to “no” quickly. We want candidates who wouldn’t like this job, and who would prefer something else, to opt out of our hiring process as early as possible. Which will mean, for many candidates, reading the job advertisement, shaking their head ruefully, and moving on.

Let’s tackle that second one first.

Hiring is a complex multi-dimensional matching problem between the work your team needs done, and a candidate who has work they want to do.

Finding a match is hard! A candidate will say “no, thanks” to the vast majority of job ads and recruiter contacts and hiring managers they encounter on their way to finding a new job. And you will end up saying no — or at least “not now” — to all but at most one of the candidates whose resume crosses your desk.

Those “no”s are successes, not failures, of the matching process — as long as they were for the right reasons. Out of respect for both the team’s and the candidate’s time, we want to get to those successful “no”s as quickly as possible. We want True Negatives and True Positives! This has consequences for how we communicate the opportunity (and how we evaluate candidates).

When we do too seldom advertise our jobs, often we try to make it sound as perfect as possible, and stay mum about any challenges or shortcomings. This is a mistake, and it comes from a place of fear; “why would anyone want to work here when they could work in tech; let’s just stay quiet about the salary/challenges of working with many different kinds of research groups/open-ended nature of the work…”

Not being completely transparent about the challenges of the job is a mistake. We’re hiring smart, driven people who are looking for tough challenges to be successful at. (There are many easier ways to make a living than working in research!) Our jobs are great; we all know lots of people who wouldn’t consider working in any other community. There are candidates and employees who would (and do!) not only thrive under but enjoy those challenges; prefer them, even. We want to be completely upfront about the challenges of our jobs, so that the people who would love wrestling with those problems apply, and the people who would hate it know right away. It’s the only approach that’s fair to both the candidate and to the team looking for a new team member. The alternative is to have people find out about those challenges three quarters of the way through our process, wasting everyone’s time and making the candidate feel led-on.

A classic example: one of the advantages many of our institutions have is clear and somewhat transparent salary bands. It is a mistake not to publish those (the actual numbers, not “Pay Band 8Q-17(h)’’) in job advertisements. They are a reality of the job, the candidates who make it to final stages of the process will find out about them soon enough, and not communicating them earlier serves no valid purpose. Is the job a one-year contract with renewal dependant on finding new funding? Same thing, say that too. I’ve heard this sentiment before: “our salary is low (or contract is short), but if we can get someone to learn about the job and team and really like it before they learn about the pay situation, they might be ok with it”. Not to put too fine a point on things, but this approach is deceitful and manipulative, and we should be better than that. Candidates who for whatever legitimate reason can’t or won’t work for that salary are entitled to know it before we ask them to spend time on our process.

Another example: maybe we’re hiring someone whose first responsibility will be to drive a big change effort. They’ll be getting pieces of an organization to work together, cleaning up tech debt, integrating disparate systems, taking over a struggling team, or helping a project team make the tough transition from long-timelines and exploratory to tight timelines and an execution focus. It’s going to be tough. Highlight that. Emphasize it. Candidates who are likely to be successful at that work would love to hear something along the lines of “this job will have outsized impact on research in our institution, and you’ll get support from your higher-ups, but it will be hard work with success not assured”. And it is unfair to candidates who don’t want to do that kind of heavy lifting work to not tell them right from the beginning. I personally have been both of those candidates at different times (I don’t have it in me to do two of these jobs back-to-back) and in all cases I would want to know right away.

The reason this “get to no” point is not contradictory with “job advertisements are for attracting candidates” is that a description of your job which speeds True Negatives by having people who don’t want that work opt out, will also speed True Positives, attract candidates who would like the work and could see themselves be successful in it.

I can’t emphasize enough, a job advertisement document is not the job req posted to your institutional jobs page. Your HR team, bless their hearts, have their own internal processes and requirements for having and posting job requisitions. They probably have boilerplate text that you fill in, and they have to make sure that the responsibilities you’ve written down (following their job competencies matrix) match with those of ol’ pay band 8Q-17(h). Candidates will be required to see that req before clicking on the apply button. Great. It’s HR’s job to make sure we stay in compliance with laws and their policies (not in order of importance), so let them have this. You do you, HR team!

But we can and should communicate our jobs externally in very different ways. Anything we write likely has to to link to the Official Job Req so people can apply, but we’re not bound to use the wording of that internal process-driven document in our external communications. If you talk to someone on the phone about your job, I assure you that you’re not required by law or policy to read verbatim from the job posting. Same with a blog post on your teams web page (your team does have a blog, right?), an advertisement on an external website, or anywhere else. Just make sure that your external communications funnel to HR’s job posting.

Write a clear, first-person advertisement (“I and our team are looking for”) that gives a clear view of what they’ll be working on, what success looks like, and that you have a clear view for how they’ll grow up to that initial success and how they might grow beyond. Explain what’s in it for them, what challenges they’ll face and conquer, and why it matters.

Of course, writing the ad is just the start - you need to get people to read it. Posting it on your blog and an external job board is a good start, but we’re well past the days where hitting “publish” then passively waiting for people to apply is enough. You’ll need to take a more active approach, and we can talk about that later.

Is this distinction between a job advertisment and a job requisition/description clear? Do you have a job req you’d like to see this approach tried out on? Hit reply or email me at jonathan@researchcomputingteams.org and we can give it a try.

With that, on to the roundup!

Good interviews vs. great interviews - Ravi Trivedi

Trivedi’s article is very consistent with what I’ve written above about job ads. The difference between great and good interviews, in Trivedi’s estimation, is that great interviews communicate lots of signal in both directions as to whether the job and the candidate are a good match. The interviewer gains lots of information about hire/no hire, and the candidate gains a lot of information about the job and whether their decision should be take the job or don’t take the job.

That means, for the interviewer, communicating why different parts of the process are relevant for the actual work, letting the candidates meet and talk with many of the people they’d be interacting with, and more.

Quality Is Systemic - Jacob Kaplan-Moss

Kaplan-Moss is writing here about software, but the point applies more broadly. A team producing quality output isn’t because of one or two factors, or because of some inherent quality of the team members; it’s because there’s a system in place to support and reinforce quality output.

The same is true in how are team is managed. There’s no “one weird trick” to manage an RCD team well; if there was, this newsletter could have been one single issue and we all could have saved a lot of time.

Good management - which our teams deserve, and our clients benefit from - is systemic. There’s an interlocking system of practices that make for good management. One of those practices is constantly learning what does and doesn’t work, jettisoning parts of the system that don’t work any more, and adding new parts needed to improve things.

As a Leader, You Own Your Communications Bubble - Jarie Bolander

As a manager or lead of a team, we make a communications bubble around us.

Bolander reminds us that this is not a bad thing, necessarily. All of our team members have one, too. We don’t generally want to be processing news about every ticket or line of code or user support issue or dataset. And our team members don’t as a rule want to slog through detailed meeting notes from every meeting we take with peer managers or stakeholders or funders. (Heck, generally we don’t want to, either, even if it’s a good idea).

But we as a lead or manager have a role power which means that we are singularly responsible for our communications bubble. If information isn’t making it into our bubble, that’s on us. Bolander tells us what to be on the lookout for:

If you find yourself asking questions like: How come I always hear things at the last minute? How come we never finish our goals? Why are my folks unmotivated? Why is it so chaotic around here? Then you’ve built your bubble around folks telling you the good news, holding back the bad news, and not wanting to be the focus of someone’s ire.’’

And how to fight it:

(Incidentally, Bolander’s article focusses on information coming into the bubble, but we also have responsibility to make sure information and knowledge is coming out of our bubble at the right rate, too. I’m constantly amazed by how easy it is for me to just forget to communicate things that are on my mind to the team; they are so on my mind I just assume everyone else is thinking about them, too)

Technical Evaluation of a Startup - Ian Langworth

This is a really interesting write up of an evaluation an experienced startup hand made of another startup’s technical team (they lacked senior technical leadership, and the CEO and investors wanted feedback on how thing were going). It’s a fascinating lens through which to think about our own technical practices, and it’s a a nice clear sensible writeup.

Langworth covers the team organization, technical processes, workflow, code review, technical architecture, data management, and other, with green (keep going)/amber (warning)/red (stop!) recommendations and some items for future consideration.

How to get Helpful, Actionable Feedback From Your Colleagues - Lara Hogan

Giving a peer direct feedback can feel like a bit of a risky thing - how will they take it? Will they hold a grudge?

If we want feedback from our peers, then — which we should — we shouldn’t just ask open-ended questions and hope they give us clear specific answers. We need to help them out a bit at the beginning, and give them some signals that we really do want the feedback and take it well and seriously. Over time, when they’ve seen we do take it well and seriously, it may take less effort.

Hogan suggests being very specific in our requests, picking an area to focus on and asking for input on exactly that area, e.g.:

“Something I’m working on is getting better at [skill]. Since you’ve seen [example of me using this skill], could you give me some feedback on it?”

And then taking the time to process that information and decide on next steps.

How Discord Supercharges Network Disks for Extreme Low Latency - Glen Oakley, Discord Engineering Blog

This article is about working on database storage in the cloud with GCP, but the issues and tradeoffs will be familiar in other contexts - high-speed local but (because of that) inflexible SSDs with high-latency network-attached flexible spinning disk storage.

Oakley describes Discord’s building a “best of both worlds” approach for their needs, where they needed low-latency reads. They using Linux RAIDs and logical volumes, using “write-mostly” for the high-latency disks.

Operating system upgrades at LinkedIn’s scale - Hengyang Hu, Dinesh Dhakal, and Kalyanasundaram Somasundaram, LinkedIn Engineering Blog

Here’s another familiar issue - rolling out OS upgrades. The approach and issues here won’t be surprising, but LinkedIn relies on hundreds of thousands of servers, so edge cases and race conditions come up much more often. The authors here describe the automation infrastructure LinkedIn built to support this, LinkedIn’s Operating System Upgrade Automation (OSUA).

Ask Twitter: Why don’t academic researchers use cloud services? - Chris Holdgraf

Holdgraf asked his followers on twitter who were otherwise interested in using commercial cloud services what was holding them back; the answers he got, in order of how often they came up, are below:

I’m very sympathetic to the first four reasons, which are all real and at least partly addressable. The middle three come, primarily, down to “we have built our knowledge up on other kinds of systems, not these ones yet”, and cloud knowledge is something that can usefully be provided centrally. The first issue about surprise over-spend is something a lot of people are working on getting cloud companies to address; while there are some third-party solutions, it’s still a serious issue.

I guess I’m less sympathetic to the last, because I’m unaware of any other options that somehow avoid continuity concerns or lock-in issues. Every technical decision is lock-in, and it’s a lot easier to unwind cloud spending than money spent building a machine room and filling it with equipment. Certainly I can see where a vendor turning off a service might be a concern, but “when will a vendor stop supporting this” is a concern for every technology, and heavens knows I’ve not universally been happy with (say) campus IT’s decisions on when to turn certain services or hardware off.

You’re paying too much for egress - Robert Aboukhalil

RCT reader Aboukhalil wrote up his initial experiences using Cloudflare R2 (#94) for cloud storage to save on egress, where you pay for storage but there’s essentially no charge for people downloading it:

[…] you can download some genomics data from the Telomere-to-Telomere project that I hosted on my R2 bucket at https://r2-article.robert.workers.dev (I wouldn’t be sharing this link if the data was hosted on S3 🙂).

I’m so glad to see that this technology has promise! This is, I think, going to be a very useful tool to have in the toolbox for making data widely available. It sounds like it works quite well, and Aboukhalil also provides some links to some other providers who have comparable offerings (and a workaround for the fact that there currently aren’t public buckets).

Continuing last week’s “naming things is hard” theme, AMD is updating it’s laptop CPU model-number naming scheme.

You may have seen this already - a great deep dive into how libraries compiled with -ffast-math break subnormal handling by default, and how that affects a number of python packages. Fascinating to see the lengths the author went to find (all!) the relevant packages. It’s long amazed me that so many codes that depend on certain FPU behaviour don’t set (or at least query) FPU modes at run time.

Great overview of FFTs for large multiplication, which comes up frequently in (say) cryptography.

“Enterprise Information Technology and the Department of Athletics and Recreation are collaborating on Huskies Esports…” Oh, man, I missed lettering in Zaxxon by just a few decades.

On Windows? Your file copy taking a long time? Pass the time by playing lunar lander in the copy file dialog.

An overview of POSIX, started in 1988 wth roots back to 1969, and why it may be time to move beyond POSIX in the future.

Difftastic, a structural diff.

Visualizing graphs with a million nodes in the browser with WebGL.

An article with great visualizations about why a (rightfully) poorly known pseudo-random number by von Neumann is so poor, and about desired properties of good PRNGs in general.

In praise of the features of Perl 5.36, if you’re into that, which you shouldn’t be.

Nice overview of taichi, a compiled Python DSL. It’s great that there’s growing efforts to make Python fast! I think the comparison to Numba isn’t quite fair to numba though, whose JIT is more powerful than the article suggests. Has anyone played with the two and has opinions they’d like to share?

Build simple retro in-browser games easily with WASM-4, which looks like a lot of fun.

SiFive’s RISC-V CPU is going to be a standard NASA space flight processor - cool!

When using huge pages for code can improve performance for complex codes.

Profile-based optimizations used to be really big in the 90s, and seems to have largely vanished from the collective conciousness since. Connecting with the pervious item, here’s how using clang’s BOLT optimizations for code layout can speed up clang by 15%.

Sign your github commits with your ssh key.

And that’s it for another week. Let me know what you thought, or if you have anything you’d like to share about the newsletter or management. Just email me or reply to this newsletter if you get it in your inbox.

Have a great weekend, and good luck in the coming week with your research computing team,

Jonathan

Research computing - the intertwined streams of software development, systems, data management and analysis - is much more than technology. It’s teams, it’s communities, it’s product management - it’s people. It’s also one of the most important ways we can be supporting science, scholarship, and R&D today.

So research computing teams are too important to research to be managed poorly. But no one teaches us how to be effective managers and leaders in academia. We have an advantage, though - working in research collaborations have taught us the advanced management skills, but not the basics.

This newsletter focusses on providing new and experienced research computing and data managers the tools they need to be good managers without the stress, and to help their teams achieve great results and grow their careers.

This week’s new-listing highlights are given below in the email; the full listing of 209 jobs is, as ever, available on the job board.