I get a lot of questions about both hiring and communicating expectations/performance management. I’m trying to compile and clean up some of what I’ve written on those topics (e.g. #65,66,67,68) in an ebook like I put together for one-on-ones at the beginning of the pandemic.

There’s two big topics left on the topic of communicating expectations; they both touch on the current top un-answered question on the pol.ly poll:

How can I get better at receiving feedback from my team?

A lot of what we see about expectations management and feedback is about managers providing feedback to individual team members. It’s an important topic! A hesitation to give routine feedback (frequent, mostly positive, always rooted in behaviour and impact) is the biggest gap I see among new managers of research computing teams. This is an vital “beginning as a manager” 101-level skill. It’s also one scandalously overlooked and under-appreciated in most of our institutions.

But it can’t stop there. The 201-level of management is to start thinking in terms of the team collectively as a system, one that has its own momentum and dynamics. As an IC in technical work, you built machines which did things - computer or software or data management systems. As a 101-level manager you support and direct individual machine-builders, maintaining individual relationships with them, and supporting their professional growth. (And to be clear - in my experience a solid 101-level manager is already comfortably in the top 1/3 of managers of RCD teams). Your 201-level skills build on the pairwise manager-team member relationships you build and maintain with management 101 skills. As a 201-level manager you are are growing, nurturing, and tending to an organization which consistently and reliably builds the right things well. You’re developing a self-sustaining team of machine-builders.

There are both 101 (individual) and 201 (team) level components to getting feedback from your team-members. In both cases, the feedback is valuable for both effectiveness reasons, and for modelling the response to feedback you want to see.

(An aside; there are excellent management resources which say that you can’t get feedback from your team members in the same sense that you give feedback to them. They mean something quite specific about feedback, which includes a requirement to change a behaviour. You can require things of team members in a way they can’t of you, because of the power difference and because you have work responsibilities other than to them. This is all completely true! I just don’t find it particularly fundamental. You want to constantly be soliciting input from your team members, and from the team as a whole, and incorporating that input into changes wherever possible. By all means call the input you collect and the process by which it’s given something other than feedback, if that works better for you. I’ve not found reifying the distinction with different terminology to be useful. Your team members are already well aware that there’s power and scope differences between their role and yours.)

Working with individual team members and asking for their feedback consistently is important for developing the working relationship, and for modelling the feedback process for them. Your team member will, reasonably enough, initially be extremely uncomfortable offering you any kind of constructive feedback (and maybe even positive feedback, for fear of not wanting to sound like they’re sucking up). As in Hogan’s article about getting good feedback from peers last issue (#136), the key is specificity and consistency. Repeatedly asking in every one-on-one about something you’re working on for a few weeks, or a new process you’re trying, is a good way to get started. “For the next few weeks, I’ll be working on improving how I run our meetings. Do you have any feedback for me about those meetings - things that work well when I do them, things that could be better?” When they, inevitably, say “No, everything’s fine” the first few times, respond with something along the lines of “Ok, well if you think of something, let me know over slack, or we can talk about it next week”, and then follow up next week. Keep asking exactly the same question a few weeks in a row and following up.

Ed Bautista also makes a great point about asking for feedback even in the process of giving challenging corrective feedback to team members. If this is something that’s come up before, and change isn’t happening, it’s worth asking “Is there anything I’m doing that’s part of the problem, or something I should be doing to help you with this change?”. From his article:

[…] behavior is adaptive, and when we encounter behavior we view as problematic we should get curious about what the other party is adapting to–it may be us. So even in a conversation in which critical feedback has been accepted without defensiveness and amicable agreement has been achieved, it’s worth including this step in the process.

Again, this is important both for the relationship, for modelling receipt of feedback, and for your own effectiveness.

When you do finally get feedback for you from the team member, this is a cause for celebration! Now we need to make sure we’re modelling the behaviour we want to see, and behaving in a way so that we’ll get more of it. The key steps are:

Do not get defensive (which can be hard), start justifying why you can’t change the thing (even if you can’t), or for heaven’s sake telling them that they’re wrong. The goal here at the individual level is for them to bring up problems to you readily, confidently, and promptly, and for you to model the receipt of feedback. Remember that if they see a problem and bring it up to you, there probably is a real problem, even if it might not be quite what they’ve identified. Dig in, give what they’ve said real thought, and be prepared the next time you talk to talk about mitigations even if the cause they present is something you can’t or won’t change. Work with them on at least some way of addressing the issue.

Doing this a few times, even if the changes made aren’t exactly what they raised, will demonstrate that you take their input seriously, even if you can’t always do what they ask. This builds a level of trust that is difficult to develop otherwise.

Once this is established at a one-on-one level with your team members, building a culture of feedback at the team level is the next, 201-level step. There’s two big levers for - team retrospectives, and encouraging team members to give each other direct feedback.

Retrospectives - time set aside for the team to think about the performance of the team as a whole - are as foundational to 201-level management as the one-on-one is to 101-level. Your team members can’t put careful thought into working on the team while they are are busy working in the team, focussed on the details of their individual work.

The team (including you) needs to be able to establish its own internal expectations. The team needs to be able to set and improve team processes so that work gets done effectively and well. Team members also need to learn what holding other team members accountable for shared expectations looks like. (I can not emphasize this enough. A team is a group of people that rely on each other, which necessarily means that they hold each other accountable. That reliance and accountability is what turns a group of people with the same departmental mailing address into a team). Retrospectives is where work on the team happens. As the manager, you have an vital role to play facilitating that work! But the more that the work is driven bottom-up by the team members, the more likely it is to become self-sustaining.

Some kinds of work, like software development with short (few-week) sprints, lends itself to frequent retrospectives. Other kinds of work may not present natural opportunities for retrospectives other than the occasional completion of big projects. In that case you’ll have to make the opportunities — which can be a simple as a periodic recurring agenda item at staff meetings.

Either way the approach is the same. Once you’ve established two-way feedback trust with each of the team members, you’ll make use of that trust to get genuine input on how team-wide things are going, what should be changed, what’s working well and shouldn’t be changed, where there’s unnecessary friction. At the beginning, the input will likely be safely and superficially procedural (“can we skip standups on days where we have the staff meeting?”). which is fine. It’s a start, and procedural issues need tending to. Initially, these will be comments on processes that you set up. As with the individual level feedback, how you respond, and the team discusses and responds to these issues raised will build trust. And you’ll get to build your meeting facilitation skills, helping the discussion progress without driving it or necessarily even contributing very much.

Over time, the retrospectives will start to touch more on shared team expectations. Things like ticket or pull request response times, what’s needed for an adequate a code contribution or data curation task. The sort of expectations that team members can hold each other accountable for. As consensus builds around these things, they should be documented somewhere the team can refer to and update. This is not only something the team can hold itself to, it will be an important resource in onboarding new team members.

The other team culture of feedback lever you have on your disposal will come up in one-on-ones. Not all the feedback you get will be about you; you’ll start to hear how another team member didn’t meet some (collectively or individually understood) team expectation. Generally this is not something that benefits from your direct involvement (e.g. #55 on “triangulated feedback”); this is an opportunity for you to coach the team member on giving the feedback directly to the other team member, and debriefing on how it went. Having modelled this already for your team members will support this, as will team discussions in retrospectives.

None of this is easy - it takes time, and requires building multiple layers of skills on your part. Skills include individual-level feedback skills, meeting facilitation skills, and a lot of listening, empathy, and governing any immediate reactions you may have to feedback that you receive about your own work or processes you’ve set up. But the reward is a team with its own momentum and increasingly self-sustaining culture,

What do you think - where have you seen this team-level accountability work really well, and where have you seen it struggle? Anything you’d want to add or share for the other readers? Let me know - just hit reply, or email me at jonathan@researchcomputingteams.org!

And now, on to the roundup!

Group Dynamics: The Leader’s Toolkit - Ed Bausta

Very apropos to the discussion above, Bautista covers some of the levers available to you for shaping the group dynamics of a team:

Bautista has a lot of very useful links to his own writing here, broken down by those topics, it’s well worth digging into if you want to learn more. Much of what Bautista writes is for higher-ups, rather than managers of ICs, but the team and individual management issues he covers are the same at all levels; we’re all just people trying to get our work done together and have an impact.

Bautista points out that “the group” under consideration at any moment may not be the same as “the set of people who have you as their manager”:

In an ideal world, everyone who reports to you is a member of the team, and every member of the team reports to you–but organizational life isn’t always so neat and tidy.

which leads us very nicely into the next item.

Task Forces - Aviv Ben-Yosef

Our work is inherently collaborative and multidisciplinary. That means that we often tackle work that needs expertise and people from different places on the org-chart, assembled for some ad-hoc purpose. I personally hate terms like “task forces” (or, heaven help us, “tiger teams”), but we need to call them something, and talk about how they should function.

Ben-Yosef advocates for keeping them tightly scoped, running them professionally, and keeping the formal managers and teams connected to the task force members:

The leader’s journal: Become an inspiring leader in ten minutes a day - Ofir Sharony

How to Learn From Your Failures - Jeremy Adam Smith

Retrospectives aren’t just for teams!

I’m not sure if “becoming an inspiring leader” is necessarily something we need to aspire to, but Sharony is exactly right about the need to take notes and reflect constantly as a manager:

We make dozens of decisions every day, but rarely get immediate feedback on them. Unlike developers, who can write code and see its effect on users within minutes or hours, leaders rarely see the consequences of their actions until weeks or even months after a decision is made.

To give us some way of learning in the sensory-deprived environment (#115) of management, we need to record what happens so that weeks or months laters as things do play out we have some hope of connecting that to our actions. We don’t get ticket systems or version control or architectural decision records anymore to faithfully record what we’ve worked on; instead we have to do it ourselves.

Sharony suggest setting aside 10 minutes towards the end of day to take some notes on creations, decisions, insights, and challenges from the day ending, and how to make the most of the next day, and to review and reflect on those periodically.

And Smith suggests spending some time to reflect, at some emotional distance, from things we’ve done that haven’t worked, put that in some context, and build from that. The article has a number of research-based recommendations for doing that constructively, without beating yourself up over it, including by focusing on learning as the goal.

By the way - learning from failures is important, but we know (#104) that for teams at least, learning from successes is just as important; teams that focus retrospective time on both things that went poorly and well learn faster and do better. So pay attention to mis-steps, but to successes as well!

Implementing Open Science at University of Utrecht (Twitter Thread) - Jeroen Sondervan

In this twitter thread Sondervan describes the multi-pronged, multi-year, comprehensive approach being taken at Utrecht to make Open Science a default choice. Changing behaviour at an institutional scale is incredibly hard, and Sondervan’s overview is well worth reading.

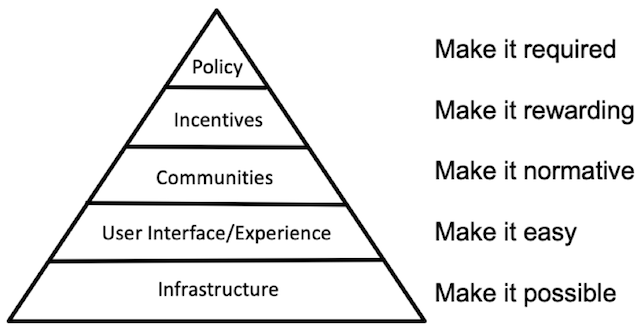

One diagram I really like is Nosek’s Strategy of Culture Change, suggesting a “Maslow’s Hierarchy” of needs for any cultural change, ranging from infrastructure (“make it possible”), and building on that foundation UI/UX components (“make it easy”), Communities (“make it normative”), Incentives (“make it rewarding”), and only then at the top Policy (“make it required”).

How does the space influence Living Labs? Evidence from two automotive experiences - Della Santa, Tagliazucchi, and Marchi, R&D Management (2022)

As with the above open science effort, our teams often have goals of enacting change in an institution - promoting open science, or better scientific software, or more efficient computing, or better and FAIRer data management, etc. For really big efforts, a lot of thought is put into what kind of physical space best supports the interactions that lead to that change.

This work by Della Santa et al, looking at two automotive R&D efforts that were intended to lead to change in their communities, suggests that there’s no silver bullet. One facility was more separate, where practitioners had to actively leave work to participate there and there were lots of co-working spaces; the other was more open and closer to where the practitioners were, making it easy for people to come visit and learn.

Both were successful, but in different ways. The more closed facility facilitated more deep work and longer engagements, but there was a barrier to entry there so that only very interested people engaged. The more open facility enabled more engagement, and a wider range of practitioners participated and learned, but there were fewer long term deep engagements. Which is better? It depends on what you’re aiming to achieve.

RSE International Survey 2022 - Hettrick et al

Here’s a summary of an RSE survey with data collected by RSE societies (formal and informal) internationally.

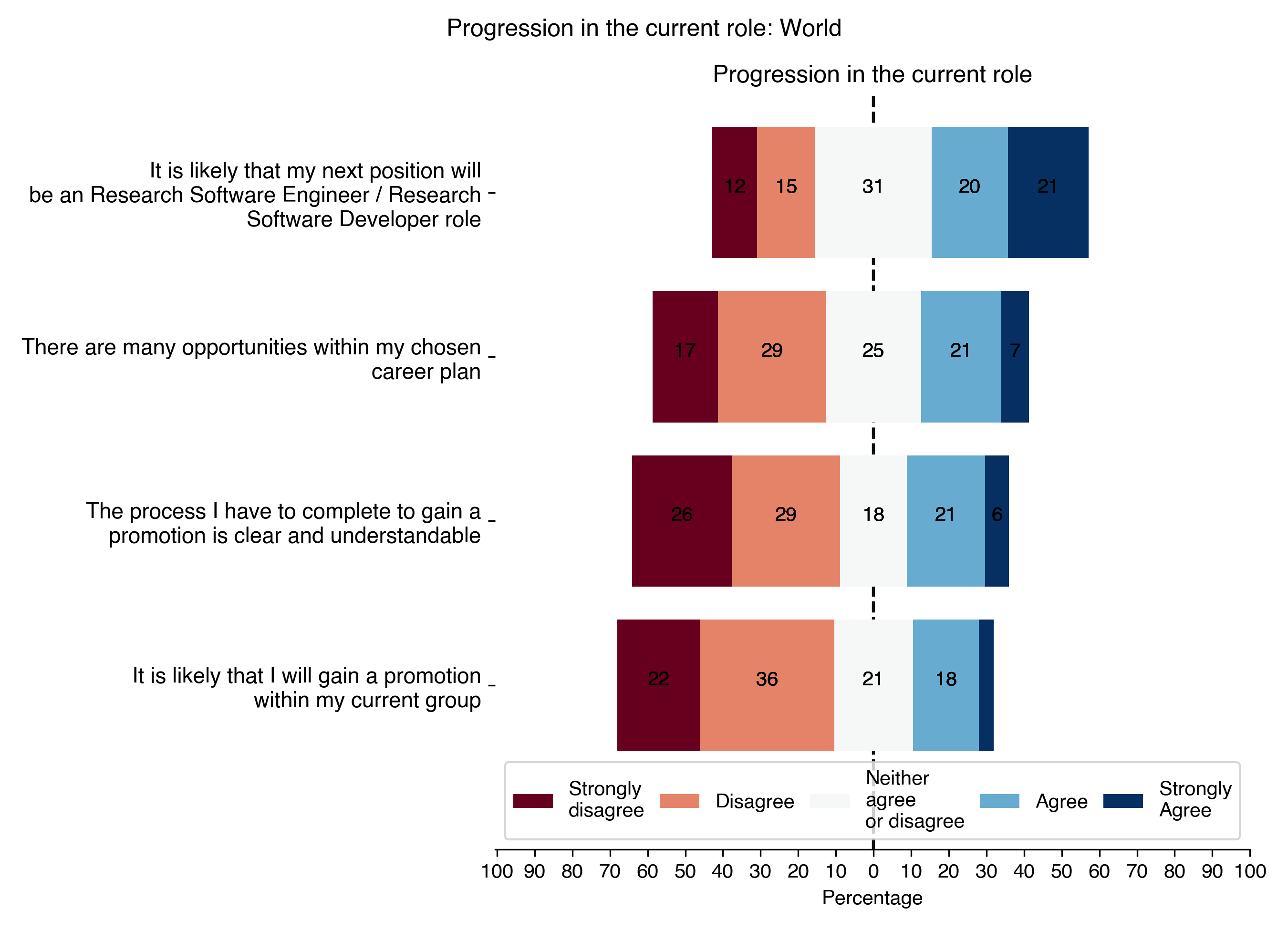

There’s a lot of good stuff here; people are by and large satisfied in their work, which is crucial. The ongoing lack of diversity in the profession remains an issue, with the field being overwhelmingly male. There are also issues with lack of training and lack of credit, and very serious issues about job progression (see the diagram below - 28% feel there are many opportunities available, 27% feel that there’s clear steps for promotion, 20% feel they will get a promotion in their current group, and 27% feel their next job will be in this sort of role). I’d imagine issues with career support compound diversity issues; if we’re going to hire people and offer them little support, credit, or growth prospects, there’s going to be an issue with getting a broad spectrum of participants.

This may be interesting for those who might be called in to help manage an institutional or domain research software registry or catalog: Nine best practices for research software registries and repositories

Which fonts to use for your charts and tables - Lisa Charlotte Muth, Datawrapper

Muth has a nice, clear, actionable set of recommendations here for font choices for data visualizations.

Social Sciences & Humanities Open Marketplace - DARIAH, CLARIN and CESSDA EU Data Infrastructures

A set of three EU Data infrastructures have put together a curated, community-led listing of resources (software, data sets, training materials, publications, best practices workflows) for the social sciences and humanities community. Open source, proprietary, and everything in between is listed, and the registry is updated regularly. A very useful resource.

Using incidents to level up your teams - Lisa Karlin Curtis

Running More Low-Severity Incidents Is Improving Our Culture - Dan Condomitti

Curtis tells us that her company’s professional handling of incidents (downtime, service degradation, data loss, etc) and including juniors helped her to learn and grow professionally, in a number of ways. Not only did she learn how to debug and solve problems from the best, but also learning the whole stack, how to build resilient systems, and growing the network of people she new at the company was useful. She talks about what a good incident-handing culture looks like, being transparent and communicative during the incidents, and making sure that there’s no single “hero” handling the burden.

Another point she makes and the subject of Condomitti’s article is that as with many things, you get better at doing something if you do it more often. That’s true from giving feedback to hiring to handling incidents. Curtis and Condomitti both recommend significantly lowering the threshold to declaring an incident, so that your incident-response handling muscles stay exercised.

The northern hemisphere academic year is starting back up, plus there’s more events then there was this time last year or two years ago. Introverted and feeling dread? Here’s a collection of articles to help.

Using cloudflare R2 (or other low-egress-fee object storage) as an apt or yum repository.

The last person in the floppy disk business; apparently business is good!?

Stand up an ssh server which lands people in a newly spun up container.

Can we please move past Git? Not yet, it seems.

An elm/mutt inspired terminal email reader with support for multiple accounts - meli.

A couple “weirdness of large deep learning models” items:

Distance in high dimensional spaces, text-to-image models, and macabre ghosts in Stable Diffusion. (Heads-up: This thread is interesting and mathy, but the Supercomposite thread it quotes has some disturbing images if you follow it down a while).

Deployed models like GPT-3 can be told to ignore the instructions they’re to follow: welcome to prompt injection.

And that’s it for another week. Let me know what you thought, or if you have anything you’d like to share about the newsletter or management. Just email me or reply to this newsletter if you get it in your inbox.

Have a great weekend, and good luck in the coming week with your research computing team,

Jonathan

Research computing - the intertwined streams of software development, systems, data management and analysis - is much more than technology. It’s teams, it’s communities, it’s product management - it’s people. It’s also one of the most important ways we can be supporting science, scholarship, and R&D today.

So research computing teams are too important to research to be managed poorly. But no one teaches us how to be effective managers and leaders in academia. We have an advantage, though - working in research collaborations have taught us the advanced management skills, but not the basics.

This newsletter focusses on providing new and experienced research computing and data managers the tools they need to be good managers without the stress, and to help their teams achieve great results and grow their careers.

This week’s new-listing highlights follow in the email edition; the full listing of 210 jobs is, as ever, available on the job board.