Teams are having a hard time hiring - or even getting people to apply for their jobs. Whenever groups of research computing and data managers and leaders get together, this is a topic that comes up - I’ve heard it as a common refrain in the past year especially.

Unfortunately, the old approach of academic hiring - post a templated job description on a website and wait for the candidates to find the job and send in an application - doesn’t work any more. It doesn’t work anywhere particularly well, but it falls especially flat in our industry. You see this everywhere across academia; even what used to be highly competitive postdoc positions just aren’t being applied for.

We have to be more active in searching for job candidates today. That means a lot more work, but it’s upfront work which will make the hiring and onboarding earlier.

(We also have to be more active and put more work into retaining team members - I’ll talk about that next week)

The most immediate problem, and the one most commonly cited, is this: With the growth of interest in technical software, AI/ML, and data science, there is an increasing demand for the skillsets we need, but a limited supply of candidates. While our jobs have meaningful work, opportunities to learn and flexibility, we can’t offer the same salaries as industry (which are frequently 2x-3x of our salary bands).

And that’s certainly true - but even without the very recent rises in salary and demand, the old “post a job ad and wait for the applications to roll in” model is less and less relevant in our digitally connected age. Its biggest problem is that it can only possibly reach that small fraction of people who happen to have started an active job search right around the time your job ad went up. Even then it’s just one ad, probably not very well marketed, among a sea of others.

In the meantime, recruiters are actively contacting possible candidates, in every industry, before they even get to the point of actively looking. You probably know this already; if your LinkedIn page is even remotely up to date, you’re getting cold contacts fairly routinely. (If you’re not, and you’d like to be, email me). The junior people who are doing more hands-on work are getting inundated.

That doesn’t mean there’s nothing we can do. Quite the opposite! But it does mean we need to put in some effort.

Our jobs, if I may be so bold, are awesome. Yes, we have lower salaries; but people primarily driven by income have never really been drawn to research. We have meaningful work, flexibility, opportunities to learn in a wide range of fields, and we can contribute directly to work advancing the forefront of human knowledge. For on-campus jobs we have pretty bustling campuses teeming with activity and talks and events regularly available; for remote work we offer the comfort and flexibility of working from home while being part of an international research community.

But just like in research where we’ve all had to learn that the work does not speak for itself, neither do our job openings. We have to put the work in to speak, on behalf of the job opening, to the people most likely to be good candidates.

I’ve written elsewhere about job ads (#135, #136). I’ll assume that you have a good job ad, one that effectively conveys the positives and challenges of the job, that describes expectations about accomplishments, and that doesn’t list as requirements things you don’t actually require.

The next task then is to get that job ad in front of people you want to read it.

Understand the personae you’re trying to reach

To do that we need to figure out where those people might already be in their careers, what they’re reading, and how to get our ad into what they’re reading.

Our jobs are probably principally of interest to those with one foot already in the door of research or academia, so that narrows down things slightly. Who are the people, in and around the world of academia and research, who would have the combination of interests and prerequisite skills to be able to do this job with sufficient onboarding? Start coming up with some candidate personae - at least three - that would describe different situations and backgrounds of people who might make good candidates. Do not limit yourself to people on fairly traditional research computing and data paths - look a little beyond this.

Once you have these, for each candidate persona, where are those people likely to be? What would they be reading? The best way by far to find that information out is to talk to members of those groups (or people who were recently members) and just ask them. That includes members of your (or other) teams, if relevant. If you don’t have that knowledge, you’ll have to resort to trial-and-error:

You’re aiming for targeted broadcasts - mass media but carefully aimed at groups that might contain strong candidates. This is much better than just putting up an ad and sending it to an email list you’re already on (since you aren’t likely the ideal candidate for this job, you already being on a list is actually evidence that it’s not a great fit). But there’s stronger approaches to move to next.

Directly contact individuals

The above targeted but still broadcast-based methods are better than nothing, but it’s important as much as possible to directly contact individuals wherever possible. How many email blasts to mailing lists do you delete unread, or after a cursory scan, each and every week? You’ve worked hard to get the job requisition open for your new position, and spent real effort hashing out your job ad. Sending a mailing list post exciting job opportunity is just adding another piece of email jetsam to the choppy, junk-filled seas of good candidates’ inboxes.

Start with your existing professional network, prioritizing people working in the field - including people managing the kind of work that would be done in this role, but especially including people you’d secretly like to hire for this job. In an individual email, ideally referencing something specific about them, tell them you’re hiring. Give them a cool one-sentence description of what this job is and why it’s different from a generic job of its sort. Tell them you know they’re really strong in this area, and ask them if they know anyone who you could contact about the job. They may well have people in their own network who are actively looking that you don’t know about; or they may have been thinking about new opportunities themselves.

(“Jonathan, are you suggesting poaching team members?” No, I’m not: because smart, driven, capable people aren’t quails; nor is letting someone know about a cool opportunity the same thing as hunting and trapping them.)

After those direct contacts from people in your network, will come directly contacting strangers who might be interested. The place to start there is with the personae descriptions you created above. That means searching online for people who might make good candidates, on the public web with your favourite search engine, and using paid tools like LinkedIn Recruiter Lite. (Yes, LinkedIn pro costs money, and more importantly, these approaches take time. But as a manager, you are in part a recruiter; that’s part of the job.)

Given your personae, it’s time to start crafting searches that will identify those people, and then sending the same kinds of emails you sent to your network. Short, customized emails, identifying the job, making the connection to things they do, and asking that since they’re quite knowledgeable about this sort of work if they know anyone who would be interested. The response rate for these emails will be much lower than in your network, but won’t be zero.

Your institution may have some internal recruitment people who can help with this. It may even be possible to get some budget for external recruiters. This isn’t a panacea - we’re hiring for super specialized roles - but people who do something day in and day out get good at it much faster than we can if we’re doing it in dribs and drabs. Find out from your organization, or HR, if such support is possible, and how much it would cost. (Multiple months of salary for the role is a common). The work you’ve already done in preparing persona will make it much easier to work with a recruiter.

Whether you’re putting in the time or paying for someone else to, this is a lot of work. Is there an easier way? Well, there’s good news and bad news…

Make it easier the next time

There are some things you can start doing now that won’t help right away for any current opening you have, but will make finding people easier for your next job opening. They all involve increasing the visibility of your team, and developing a bench of contacts and possible candidates. And they all have knock-on effects well beyond just hiring.

First, make sure your team’s work is as visible as possible. This is valuable for career development of your team members, for attracting possible clients and collaborators, and provides concrete things you can point to when describing how awesome working in your team is:

Next, as part of you and your team’s normal professional conversations with people, build a network, and keep a constantly updated list of people you’d be interested with working in the future. Get everyone in the team to contribute

People in research computing and data are disproportionately introverted, so some of the communications and networking tasks above may not come naturally. That’s ok; I wouldn’t have to keep advising people to do it if it came naturally. Managing people well and with professionalism takes work, some of it uncomfortable.

Finally, grow both your hiring muscles and your network by having a regular practice of hiring interns, summer students, co-op students, REUs, or whatever they’re called in your institution; not only does this improve processes around recruiting and hiring, it builds a network of smart capable motivated young people, people who have friends and networks of their own, who can apply for or at least help share the good work about your job.

Do you have questions about hiring, recruiting, onboarding, or retention? Send me an email (hit reply if this is in your inbox, or email me at jonathan@researchcomputingteams.org) or schedule a call.

With that, on to the roundup for this Hallowe’en weekend. I hope this week goes well for you and your team dismembers, your meetings are (re)animated, and you achieve all your ghouls.

Group Dynamics: Very Loud (and Very Quiet) People - Ed Batista

This is a pretty common problem in research, in my experience - on average our teams tend towards the quiet, but it’s pretty common to have one or a few team members or visitors who are very talkative. Without meaning to — and without any ill intent necessary — an outlier on the talkative side will completely dominate group discussions. Similarly, if the team were tilted the other way, an outlier quiet person would go completely unheard. Either way, resentment can build up, on both sides (“Why does X always hog the discussion”/”Why does Y never contribute, do they think our team meeting is beneath them?”)

The approach I preferred early in my career, hoping the problem goes away, turns out not to work! The alternatives require intervention of some sort. Batista goes through the options:

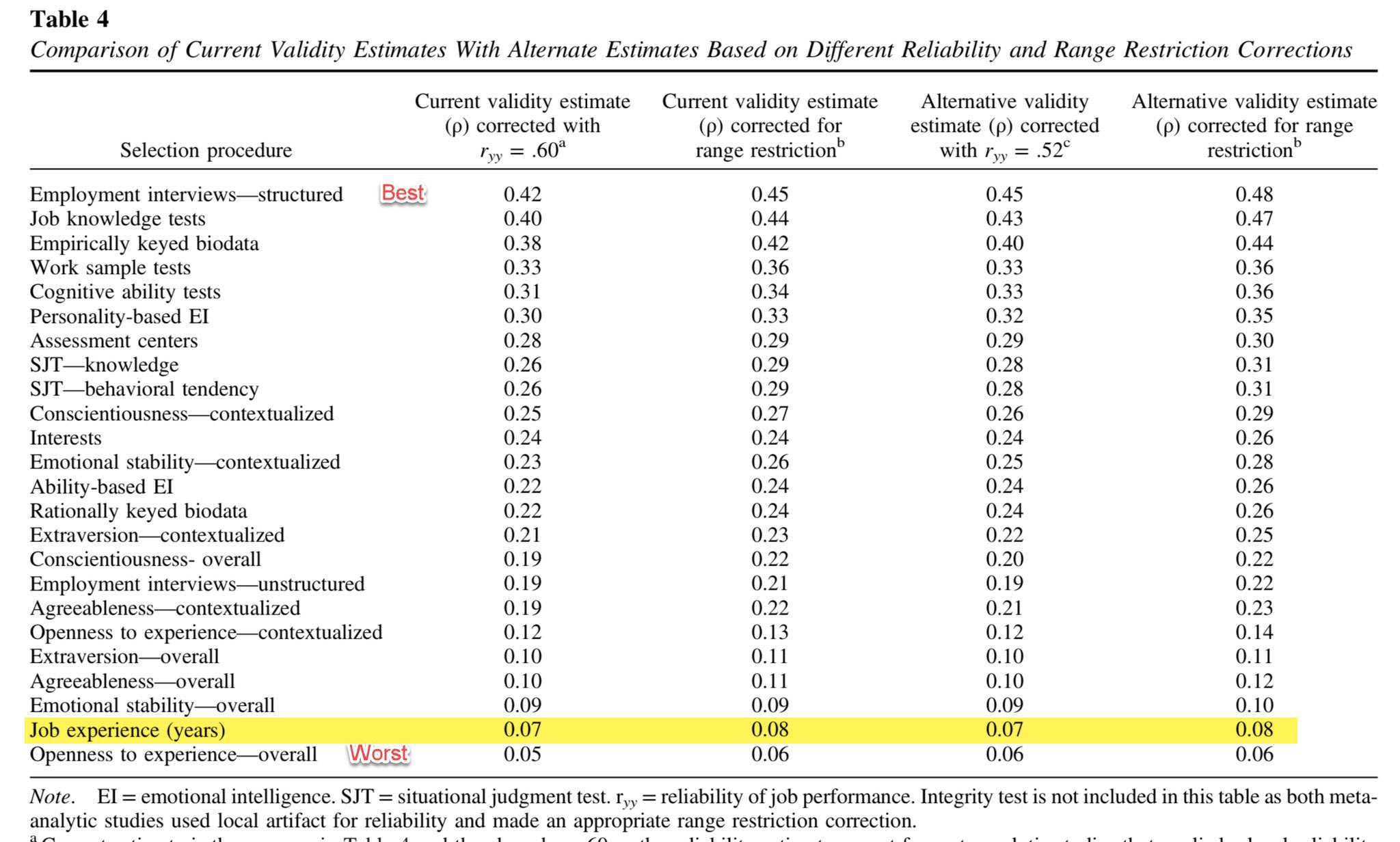

Revisiting meta-analytic estimates of validity in personnel selection: Addressing systematic overcorrection for restriction of range - Sacket et al, J. Appl. Psych

One of the points I want to drive home in this newsletter is that people study what does and doesn’t work in management a lot; of course they do, there’s a lot riding on it! It’s not all opinions and just-so stories.

Here the authors do a metastudy looking at what most and least correlates with future job success for job candidates. Years of experience is a pretty definitive second-last of all the options. Boringly professional things like structured employment interviews and job knowledge tests are top.

I don’t want to know whose fault it is - Jonathan Hall

Blameless isn’t only for incident reports/postmortems! As a technical leader, the responsibility for the structure and context in which a mistake happened is yours. Assigning blame for something that went wrong short circuits the real work that has to happen, improving the structure and context. And besides,

Except perhaps in some cases of malicious action, no single person is ever at fault.

How to work with difficult stakeholders - Neil Turner

The context here is product user experience, but the approaches here are pretty widely applicable:

How to Build Software like an SRE - Brandon Willit

When I started my career, research software was command line tools that one launched, they ran to completion, and then were done.

Now that we have long running services that people depend on, a lot of teams are struggling with writing code that supports good uptime. That means predictability.

Willit describes how SRE teams write software, and maybe counterintuitively, he describes a fail fast approach; don’t do fallbacks, don’t do heroics to retry failed steps - fail fast and cleanly, leaving a predictable and easy to understand and replicate error.

Hacks to Help Open Source Leadership Support Inclusion - Jennifer Riggins

Almost all of diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging work is hard, time-consuming people work. But, Riggins says, that doesn’t mean we can’t use some tooling to make that important work easier for open source maintainers:

PDEBENCH: An Extensive Benchmark for Scientific Machine Learning - Takomoto et al

PDEBench GitHub Repository - Takomoto et al

I’m pretty late to this game, but I’m really excited about how far things have gone in deep learning for PDEs. Being able to tweak a parameter and instantly see updated simulation results is what I imagined 2020s-era simulation would be back when I was an undergrad in the 1990s.

Moving from craftwork to science, from one-offs towards widely usable tools, means creating benchmarks and rigorously testing approaches. Here’s a first benchmark, comprising problems those of us who have spent years in the PDEs world will recognize, for developing such future work.

Cool set of short case studies of large-scale migrations.

Cool bash for bioinformatics online tutorial, for a very specific use case - running DNAnexus pipelines. Note how it’s possible to get really deep really quickly when the material is for a specific use case; yet a lot of the material could still be incorporated into other tutorials.

The HTTP crash course nobody asked for.

This is pretty neat - run cloud style data pipelines (including ML pipelines) on top of Slurm (but also Airflow, Argo, Kubeflow, Argo) with Soopervisor.

I’m having fun going through Xanadu’s Quantum Codebook tutorial. I’m learning a lot, for sure, but also on a meta level admiring the technical and pedagogical work that’s gone into the resources. It’s quite nicely done.

And that’s it for another week. Let me know what you thought, or if you have anything you’d like to share about the newsletter or management. Just email me or reply to this newsletter if you get it in your inbox.

Have a great weekend, and good luck in the coming week with your research computing team,

Jonathan

Research computing - the intertwined streams of software development, systems, data management and analysis - is much more than technology. It’s teams, it’s communities, it’s product management - it’s people. It’s also one of the most important ways we can be supporting science, scholarship, and R&D today.

So research computing teams are too important to research to be managed poorly. But no one teaches us how to be effective managers and leaders in academia. We have an advantage, though - working in research collaborations have taught us the advanced management skills, but not the basics.

This newsletter focusses on providing new and experienced research computing and data managers the tools they need to be good managers without the stress, and to help their teams achieve great results and grow their careers.

This week’s new-listing highlights are below in the email edition; the full listing of 189 jobs is, as ever, available on the job board.