When I talk to team managers and leads, individually and in groups, I often say something along the lines of our mission, as RCD leads, is to advance science as much as possible given our priorities and finite resources. I’ve yet to receive any push back on that; everyone agrees.

But it’s really only the best teams that I’ve seen that manage themselves as if that really is their goal.

If our mission is to have as much impact on science as possible - and I believe it is - then that mission has to shape strategy and decision making throughout the team. It has consequences for what work we take on, how we do it, and how much we value learning and replicatability.

There’s a reason why I basically never talk about personal productivity. There’s lots of perfectly fine practices out there about batching activities to minimize context-switching, choosing a good to-do app, etc, and it’s all fine I suppose. I’m not against any of it, and do some of it myself.

But it doesn’t really move any needles on your personal impact, nor would your team members doing those things significantly change your team’s results.

An extra 15 minutes, or even an hour a day is a perfectly decent outcome. But it doesn’t scale. It’s linear; additive. There’s only so far you can push it; and after that it comes with dramatically decreasing returns.

Worse, a focus on productivity, with every minute being allocated some task, can lead us down some actively counter-productive paths. Perhaps a manager notices a team member (or a computer resource or..) is only 80% utilized. Waste! Inefficiency! Better shuffle some work around. I’ve seen too many teams fall fully into this trap, where everyone’s furiously busy all the time. In almost every case, much less is actually being accomplished, and there’s no slack available for the unforeseen or for growth.

We all know that it’s more important for the right things to get done than to fully occupy our time doing irrelevant work in a maximally productive way. But the urgency of productivity can be very seductive, and I’ve seen too many teams get stuck here.

So how do we know which are the right things for our team to be working on? Well, there’s our priorities, of course. But there’s another dimension as well.

If we want to have as much impact as possible on our priorities with our limited resources, fiddling around at the margins with 15 minutes here or an hour isn’t going to help significantly. Instead of purely additive, linear approaches of finding an extra few hours, we need compounding, multiplicative methods. Ways of making sure that each time our team does something, we can do it 2% or 5% or 10% better or faster or easier the next time.

This is why I emphasize things like:

as well as the emphasis on building automation wherever possible, documenting the why of decisions so we know when they need to change, and more.

These are all ways that our team can continuously get better, growing individually and collectively, doing work more easily, generating the same amount of impact with less and less effort each time.

Those processes will get a team well on their way to having more impact. Over the years I’ve seen more and more teams adopt these kinds of practices, which is fantastic!

But there’s another topic I cover often: specialization (#114). Choosing the kind of work your team takes on - and yes, we can choose - is the final, necessary, piece of having as much impact as possible.

In #127 I shared this diagram below, inspired by the great book by David Maister, the first half of which is very relevant to our teams. There’s three basic ways that teams of experts help their clients:

The most effective teams have a portfolio of offerings along that spectrum, and work like heck to move things to turn one-off “expertise” engagements into reproducible “experience” and “efficiency” engagements.

Note that not every team can operate yet all along the spectrum. Sometimes it’s because they’re too new; sometimes it’s because for one reason or another they have a lot of one type of that work that has to be done first, and only once they’ve reached a size where they’re doing enough of that work that they can work on other areas. That’s ok! It’s still worth operating as if you’re aiming to tackle the full spectrum.

Many more teams can address the whole spectrum than do. The biggest stumbling block I come across is that the expertise work is fun. It’s tackling a new and hard problem our team hasn’t seen before. We’re experts, leading a group of experts. Everyone wants to do the fun hard problems!

And there’s a place for those engagements. They should absolutely be part of the mix. But they can only be a part. Doing lots of fun and challenging one-offs doesn’t scale; it can’t. We can only get better at things we do often. We can’t possibly have our maximum impact if we’re starting from scratch on every new infrastructure deployment or software project or data analysis.

At each stage of involvement with the clients, there’s work that can be done to move future projects to the right, to make things more reproducible and efficient, to have the same or better impact the next time for less effort.

Expertise engagements:

Experience engagements:

Efficiency engagements:

And for every kind of any engagement, retrospectives (including input from the researcher), knowledge sharing, and delegation can make sure the team and the team members are growing their skills and impact.

What do you think - what’s the best way you’ve seen teams increase their impact for a given level of resources? What have you tried that worked, or didn’t? Let me know - hit reply or email me at jonathan@researchcomputingteams.org.

And now, on to the roundup!

Retrospectives Antipatterns - Aino Corry

As you know from the above, I think retrospectives are pretty key to having teams that function as teams, and they’re a vital mechanism for leverage - for each time going through something to get that much better, in a compounding way, for the next time.

But unfortunately just scheduling a meeting called a retrospective isn’t enough on its own. They have to be run well.

Corry describes some experiences she’s seen that have derailed retrospectives. There’s a helpful sidebar to the article that lays out the five key (and distinct) stages of a retrospective:

Three antipatterns she describes, with stories, are:

Over at Manager, Ph.D. I talked about “prewiring” meetings or decisions, which is just a way of saying building buy-in on your proposal while putting the proposal together.

Advice for new directors - Jade Rubick

On a recent podcast, I heard Jason Warner (who turned GitHub around after being at Heroku for years) talk about a director as being not a manager++ but a vice president–. While the titles don’t quite map to our line of work, that’s by far the best one-line description of the nature of the role that I’ve heard.

Like going from a team member to a manager, going from a first-line manager to a lead-of-leads (whether that’s titled a senior manager or a director at your org) is again a career change, not merely a promotion. Rubick covers that in some detail in a good article for anyone thinking of becoming a director.

The biggest difference is that now you’re not even overseeing the work, much less doing it.

Suddenly your success is based on how well your managers are running their projects. Your success is based on how well they hire. Your success is based on the improvements they make on their team.

All of your influence on what’s being done is with at least one other person as an intermediary. Rubick says that makes one-on-ones even more important.

The sooner you’ve mastered the basics of your own role as a manager and moved on to more advanced work like making yourself less necessary by creating the processes by which good decisions get made in your absence, the easier this transition will become.

Other key points made by Rubick:

We’ve talked with Ian Cosden and the UCL ARC team about career ladders and job levels; here’s an article by Jade Rubick outlining software job levels (junior/senior/staff/principal) but also rungs within each level. The sub levels within each title make it easier to see progress (and possibly give raises if your situation allows for that) on shorter time scales.

The Anatomy of a Central RSE Team - Matthew Bluteau, Better Scientific Software

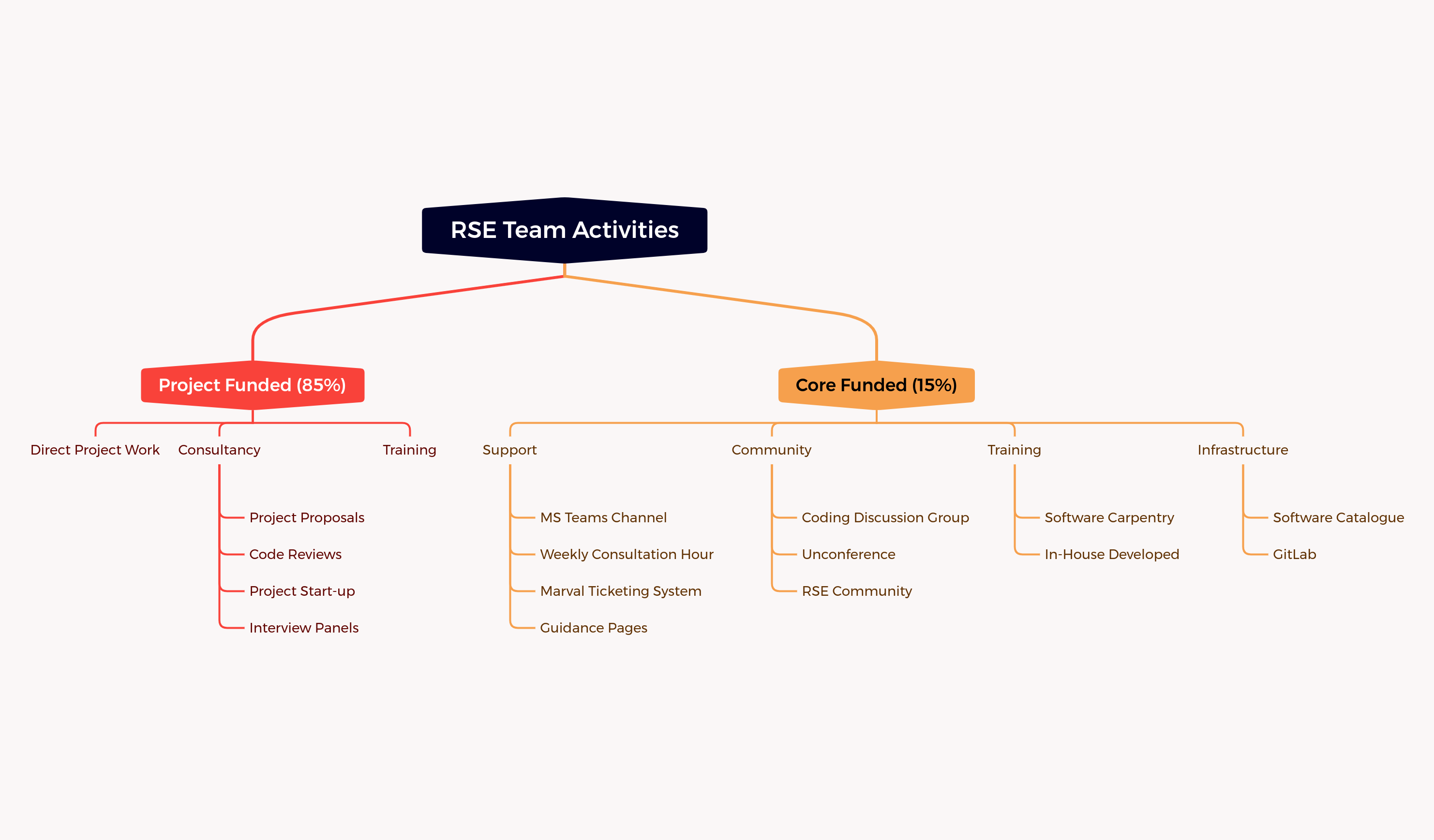

Bluteau gives an overview of how the central RSE team functions at the UK Atomic Energy Authority.

Even within the fairly specific area of fusion energy, there is a wide range of areas (and thus expertise) needed (plasma physics, materials science, mechanical engineering, CFD, data analysis, and increasingly AI). And even well-funded organizations suffer from legacy code, incomplete buy-in to good software development principals, and differing approaches, languages, etc across the org.

The team works mostly on contract work for projects funded by research teams, with 15% of its time focussing on core activiteis such as support, training, building a community, and maintaining software architecture like UKAEA’s GitLab.

Opting In to Transparent Telemetry - Russ Cox

The Go ecosystem recently went through a round of discussion about adding transparent telemetry to the go tool chain so that the go team and product management can make informed decisions. Our community has similar needs. We often need to report impact, and constantly have to make decisions about what to maintain, what to add, and what to deprecate. Bug reports and surveys just aren’t enough.

The discussion about golang transparency was contentious, at least partly because Google is so involved in golang.

Still, I think the solution struck upon as a design, especially as opt-in, could be a very useful model for the open-source science community:

The opt-in will make the data less useful, because one might reasonably suspect that use cases and opt-in status are correlated, but I don’t think anything else would be accepted by our community.

What do you think? Are there any projects you’ve seen that have data collection that helps the product team and that you think would be acceptable to the research software using community at large? Let me know - email me at jonathan@researchcomputingteams.org.

You need a (free) Adobe account, but Adobe’s podcasting service (!?!) has an easy free microphone check page which lets you know if you’re too far from the mic, whether gain is too high, and how echo and background noise is. Very handy.

More evidence from the “experience from the world of science gives you superpowers” files: new entrepreneurs taught a scientific approach to testing hypotheses perform better.

You’ve probably already seen this, but Facebook has released LLaMA, foundation models significantly smaller than GPT-3 (you can run inference on them with a single GPU) trained on larger datasets - it’s available for research use.

And that’s it for another week. Let me know what you thought, or if you have anything you’d like to share about the newsletter or management. Just email me or reply to this newsletter if you get it in your inbox.

Have a great weekend, and good luck in the coming week with your research computing team,

Jonathan

Research computing - the intertwined streams of software development, systems, data management and analysis - is much more than technology. It’s teams, it’s communities, it’s product management - it’s people. It’s also one of the most important ways we can be supporting science, scholarship, and R&D today.

So research computing teams are too important to research to be managed poorly. But no one teaches us how to be effective managers and leaders in academia. We have an advantage, though - working in research collaborations have taught us the advanced management skills, but not the basics.

This newsletter focusses on providing new and experienced research computing and data managers the tools they need to be good managers without the stress, and to help their teams achieve great results and grow their careers.

This week’s new-listing highlights are below in the email edition; the full listing of 179 jobs is, as ever, available on the job board.