“We Can’t Hire” isn’t a good enough bug report. Plus: Management Problems at ITER; Valuable Software is Updated

Over in the other place I encourage readers to use their existing scientific skills and apply them to how they work as a manager.

There’s a lot of opportunities for us to do that in this newsletter, too. Opportunities to use the skills we already have working on software or computing systems or data analyses for science to our problems in leading our teams. Interactions we’re used to having with others can be a helpful guide to fleshing out our own issues.

I’m often talking to or overhearing leads of research software, computing, or data teams while they’re describing or thinking aloud about problems they face.

And the problem descriptions are frequently at a level of fuzziness that we would never accept in a bug report or ticket from a user or a researcher.

“I can’t hire”. “The VPR’s office just doesn’t get it”. “We need more money”. “My team member is lazy”.

These are the “I tried it and it didn’t work” or “The data doesn’t make any sense” or “My jobs keep failing” of our role.

To be 100% clear, I am always happy to talk with readers at any time about their problems, at no cost. It’s ok if the question or issue is still kind of ill-formed; sometimes I can help turn it into a crisper problem statement, the sort of thing that could be a nice GitHub issue or feature request. A second pair of eyes and a sympathetic ear, especially from someone who has seen a lot of different situations in a lot of different concepts, is often a big help to anyone, regardless of the situation.

And together, we have a lot of skills from our previous hands-on work, skills that we can apply directly to these kinds of situations.

Step number one to submitting a good ticket that will get results is to have a really clear problem statement. We know how to do this.

We can’t solve fuzzy problems stated generally. We need specifics. We need to look at super concrete examples where something went wrong, and figure out at which step it went wrong.

“We can’t hire” (and equivalently, “We can’t retain staff”) is a good one to look at as an example, because hiring is a long process that involves, in addition to a bunch of purely internal stuff;

“We can’t hire”/”We can’t retain staff” could be a failure at any one or more of these steps. Somewhere we’re losing candidates or hires. Until there’s clarity about what’s wrong, which are the steps that are failing, talking about it is complaining, not problem solving.

Similarly, “The VPR/CIO/Deans/funders/whoever just doesn’t get it”. Finding agreement on priorities between ourselves and senior stakeholders is a long, complex process, and requires a bunch of things:

Again, the decision makers not being convinced by our arguments could reflect issues with any one of those steps.

When we have a few reproducers, we can see exactly at what step something is going wrong. We can look in detail at the examples and actively collect data about what went wrong. Do that a few times and we can start to see specific patterns in those problems.

Much worse than a user not having a clear problem statement is the user who is absolutely certain of what the problem is based on little to no evidence.

In the context of hiring, I often hear “industry salaries” being invoked as a reason that hiring and retaining staff is so challenging.

And yes, that difference is a real issue that exists and affects the pool of accessible candidates, but are you sure that’s the dominant problem you’re facing now? That it’s a first-order effect and not second- or third-order? How do you know, exactly? Who did you talk to? How did you test that understanding?

Remember back in #147 we covered discussion in a tech-industry discussion board about working in genomics instead of tech? In those discussions, as I said before,

Salary certainly comes up, but it’s usually mentioned as an aggravating factor, something along the lines of “there’s no way I’m going to put up with X when they’re paying me so little”.

I promise you that right now, at this moment, an equally smart and talented person to those you look for is taking a less attractive job with worse benefits at a nonprofit in your city. And a potential remote member of your team is signing up at a new startup with noticeably but not enormously better pay, vastly worse working conditions, and a near-certainty that the fledgling company will fold or lay them off within a couple of years. And someone with very similar skills that you’re looking for is accepting an offer at a local bank or other non-tech industry firm with decent benefits, somewhat better pay than you’re offering, and a stifling culture with meaningless, soul-crushing, work.

Focussing on the tech-industry salary issue is not only non-productive, it conveniently draws attention to one of the few areas you can’t do anything about, and it might not even be the dominant problem your team faces hiring. Even if it is the most important issue, almost everything else about the job, how it’s marketed, and who and how your team recruits for it, the second and third and fourth-most important issues, are something you can do something about for attracting, hiring, and retaining those people who aren’t looking for big-tech salaries.

Sometimes people will feel like it’s important to do something, no matter what, to address the problem, and will get caught up doing stuff to feel like they’re making progress, when it’s clear that what’s being done isn’t going to address the underlying problem.

For hiring, for instance, I’ve often seen people send job ads for individual contributor positions to their manager colleagues who are also having trouble hiring, possibly well away from the region they’re willing to hire in, asking to “share with anyone interested”. What is the expected outcome from this activity?

Similarly, getting precious time to talk with decision makers and using it to share detailed technical information about their work or internal operational data like utilization. What is the expected result here?

Taking interventions, even simple and easy ones, without having expectations that it will in some very specific way address the clarified problem statement distracts from the real work to be done.

Last week in Manager, Ph.D. I talked about keeping a lab notebook for our managerial work. The idea is to make a clear decision about an underlying problem, based on some mechanism for addressing it, and then record what happens so that we can learn as quickly and as systematically as possible from our decisions.

Being explicit about what we’ve tried, what didn’t work and our best guesses as to why, will help us more

And that’s that. What else have you done to try clarifying what was really the issue in a complex management or leadership situation? What worked and didn’t? Hit reply or email me at jonathan@researchcomputingteams.org.

And now, on to the roundup!

As I mentieond above, in Manager, Ph.D. #165, I wrote about using our experience with managing experiments to improve how we make managerial decisions - “Thinking In Experiments: Your Management Lab Notebook”.

In the roundup, we had:

ITER: Low morale, eroded trust and lost competence - Craig Nicholson, Research Professional News

I plan at some point a few years from now to start doing anonymous interviews of leaders significant research technical projects, doing informal retrospectives, and distilling and sharing results. I think the community really needs it, because as things stand now, we don’t have any culture at all of learning at scale from what works and what doesn’t.

Just the opposite, in fact - as long as a technical research support effort doesn’t completely fail, we only ever hear vague glowing things from the leadership and stakeholders. And when an effort does start to fail, there’s an Omertà-style code of silence that descends and we never talk about it.

Honestly, the only time we ever hear about a major technical research effort troubles is when a big multinational European effort teeters a little too close to becoming a fiasco, because (and this is a good thing!) there, there’s eventually some accountability mechanisms with teeth that kicks in when things get bad enough, and we get to see some transparency.

So I follow these stories closely, not out of a sense of schadenfreude, but because this is one of the few sources of data we have about technical research efforts struggling.

ITER has clearly been struggling for some time. One might reasonably think that it is because treaty-level multinational efforts are hard (they are!) or because fusion energy is hard (it is!).

But check out the problems described in Nicholson’s article:

Now the initiative’s European leaders say managerial and staffing shortfalls contributed to these problems, citing loss of competence in key areas and low morale as significant issues.

and

“significant loss of internal competence in some key areas in systems engineering”…. “…a loss of quality culture”… “…some lack of motivation in the staff due to unachievable objectives”.

and

“Staff morale has been low for some time,” [Barabaschi, the new DG of ITER] said.

These are absolutely bog-standard, management-101 issues. Having and holding people accountable to reasonable objectives, retaining and engaging team members, recruiting new team members, communicating openly, having a feedback culture and holding to high quality standards — this is not rocket surgery. Yes, it’s hard to remember to make sure that these basics are being focussed on in high profile efforts, when the bosses are dealing with extreme pressure from stakeholders. But that’s the job.

One of my absolute least favourite conversations, and yet one I have regularly, goes something like: “Oh, we can’t do that (absolute entry-level standards of project management, any kind of performance management and accountability, running meetings with a modicum of professionalism, regular one-on-ones, open feedback culture, career development discussions, positioning) here; this is Research, after all, ho ho ho. Maybe that kind of thing works elsewhere, but our work is far too hard and uncertain for people like us to do those things”.

“No! Stop it!”, I scream inwardly, while struggling to compose a more productive response.

It is because the work is hard, it is because the cutting edge is so uncertain, that it’s so important to do the basics right. The research we’re supporting is hard enough! Contributing to the uncertainty and challenges by failing to manage efforts and lead people like the professionals we are only makes things worse!

Science, the future, our communities, our team members, deserve better. They deserve to have the easy, everyday, quotidian things run professionally and smoothly so that only the things that should be hard are, in fact, hard.

Updated Software is Valued Software - Vanessa Sochat

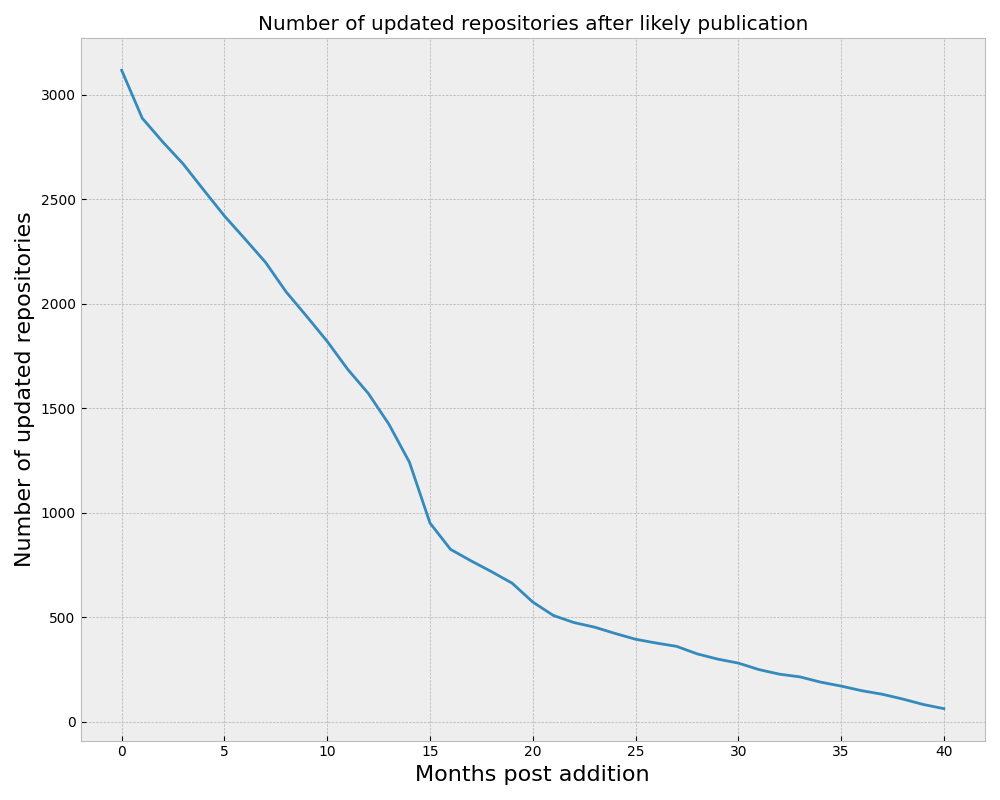

Sochat presents very valuable data, analyzing the open-source research software submitted to the RSE Encyclopedia, estimating publication date and finding out how recently the relevant repositories have been updated.

To my mind, the takeaway is this plot, showing that even amongst those packages that someone was motivated enough to enter into a list of research software, only a small fraction are still being actively updated after a year or two.

)

)

Sochat’s hypothesis is that

If a project survives a certain amount of time and is still active, it is more likely to be valued.

Which I think is fair. Sochat finds that disproportionately, the packages that tend to remain active tend to be foundational libraries or other infrastructure, (or projects with sustained funding).

This is great, and valuable work.

Sochat has kind advice for those contributors who contributed code to those efforts

I opened the post making a strong claim about the value of research software, and that it only serves a purpose in as long as it persists. I want to now say this isn’t entirely true. If I look on the work that I (or colleagues that I know well have done) it’s often the case that the large majority of our work is not successful under these criteria. “Then what’s the point?” we might ask. The point is that there is learning in the process. A failed project is not failed if you (or others) took away lessons from it.

which is excellent advice for the ICs. I think as managers charged with stewarding resources, our takeaways ought be different.

First, it’s not really a surprise that most research software goes stale shortly after published use. A very early issue of this newsletter (#11) included an article, Source Code has a Brief and Lonely Existence, showing that even within a code base, most lines of code are written, then never touched, until they’re discarded. The median GitHub repo of any sort is abandoned. Even amongst the top 50,000 GitHub repos, 15% haven’t been touched in the last year. The vast majority of research papers never get very many citations.

Second, this is not a bad thing. Research, and R&D, is exploratory. Most paths taken don’t lead anywhere particularly fruitful. But we have to try those paths anyway or else we’ll never know what’s down there. For individuals, that can be discouraging, but as a collective human endeavour, that’s just how it is. (Imagine the opposite - that every experiment, every observation, lead to something ground-breaking and new. How would we keep track of it all? How would we actually make any meaningful sense of anything in this exponentially cascading cacophony of novelty?)

But given results like this, we have to have as our prior that the most likely outcome for a piece of research software being developed is that it will most likely be run a few times, be used in a few publications, then put down and never used again.

And so we have to think about:

Even more controversially: Should we hold off on “best practices” or even “good enough practices” until we see that there’s demand for other groups for what we’re putting together?

The first issue of this newsletter, #1, had an article that I think about often, “Don’t fund Software that doesn’t exist”, making exactly this last argument - that until more than one group is actively using the software, there’s a limit to how much resources to put into developing it.

With PyTorch 2.0’s new JIT compilation, regular old numpy code can be compiled down to multi-core C++.

Building the coordinate system for an infinite spreadsheet.

SciSciNet: A large-scale open data lake for the science of science research.

The AWK book’s 60-line version of Make.

Juelich has a nice searchable collection of 589 articles and other resources on Open Science as a Discipline.

AtariLab and the Universal Laboratory Interface.

Terminal-based presentations using pandoc - patat.

Maybe relatedly - security vulnerabilities in 2023 because of CVEs in the handling of ANSI terminal codes.

And that’s it for another week. Let me know what you thought, or if you have anything you’d like to share about the newsletter or management. Just email me or reply to this newsletter if you get it in your inbox.

Have a great weekend, and good luck in the coming week with your research computing team,

Jonathan

Research computing - the intertwined streams of software development, systems, data management and analysis - is much more than technology. It’s teams, it’s communities, it’s product management - it’s people. It’s also one of the most important ways we can be supporting science, scholarship, and R&D today.

So research computing teams are too important to research to be managed poorly. But no one teaches us how to be effective managers and leaders in academia. We have an advantage, though - working in research collaborations have taught us the advanced management skills, but not the basics.

This newsletter focusses on providing new and experienced research computing and data managers the tools they need to be good managers without the stress, and to help their teams achieve great results and grow their careers.