Do the highest bang-for-buck work. Plus: What to say after a failure; GitHub Copilot’s productivity benefits; Research data services landscape at Canadian and US institutions; What modern NVMes can do.

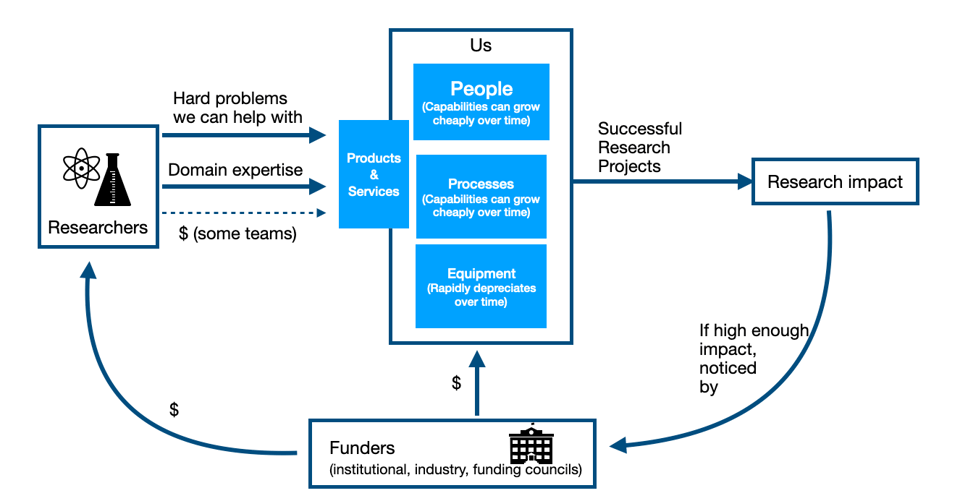

After a longer gap than I intended, I want to keep talking about this diagram, the flywheel which defines our teams’ missions.

Last issue I talked about nurturing our best clients first as a way to add work that we know is more likely to have significant research impact for a reasonable investment in our team’s time and resources.

And in fact, this idea that we should aim for the most research impact possible given our resources and constraints, a fundamental guiding principle. It has to be the beacon we steer by when making decisions.

We can use different words or phrases for this - bang-for-buck; cost-benefit; I have a mischievous habit of sometimes using the term “profitability”, e.g. the results minus the inputs, just to make people squirm.

But “Research Productivity” is probably the best term I’ve seen, for two reasons:

High Research Productivity is Our Duty To Science, Our Institution, and Our Teams

Research is scandalously underfunded. Our teams are entrusted with some of that funding. It’s our job to steward that all-too-scarce technical research support funding and resources placed under our control.

It’s our duty to science to make sure that those resources are applied to where it can do the most good, even if that sometimes means uncomfortable conversations and decisions. “But we’ve always done it this way” is not a good enough reason to put resources somewhere unlikely to pay off. Avoiding uncomfortable discussions with long-term clients isn’t a valid excuse for misallocating some of this scarce research support money.

It’s also our duty to our institutions. Most of us are in teams whose job it is to support the research aspirations of a particular institution, a particular community. For the same reasons as above we owe it to our institutions to apply our team’s efforts and our resources where it has the greatest benefit.

Finally, it’s our duty to our teams, for two reasons. One is professional pride. Our highly-qualified, over-worked, under-paid team members stayed in the world of research for a reason. They wanted to have a job that had real research impact. They have the skills and the drive to make that impact. They deserve to see their efforts have the impact they’re capable of.

And secondly:

High Research Productivity Is How We Justify Getting Resources

Our team members also deserve for their jobs to be secure, and to have more colleagues doing more things so they can be a little less overworked. They deserve to be able to grow and learn from each other, and to take on bigger challenges.

The research impact our team has is what justifies its funding.

Demonstrating the highest research productivity, the highest bang-for-buck, is the best possible argument for allocating more of those too-scarce technical research support funds to our team. It’s how we can grow our teams, and give our team members more professional growth opportunities.

The ruler we’re measured against is not “did you accomplish something with those resources”. It’s what those resources could have accomplished deployed elsewhere. The measuring stick, the unit of comparison, is the very best best research teams #173.

It may be uncomfortable to think of ourselves as vendors #123, but we are. We provide services and access to resources in exchange for funding.

In particular, we’re Professional Services firms, not Utilities (#127).

Utilities just mindlessly mass produce and provide undifferentiated power or water to whoever turns on a switch or opens a valve, and is willing to pay for the service. Utilities are cost centres, and are replicable if an alternative with lower costs come around.

But we’re professional providers of services. We bring expertise and judgement to bear, to help researchers accomplish as much impact for Science, Research and Scholarship and for our institutions. We make sure our team members can do their best work, and that the researchers can do theirs. That means applying judgement to what we work on.

Sometimes This Means Saying No or Phasing Out Work

And sometimes that means saying No to projects or kinds of work, even if would be useful to do them, even if we used to do them before.

I’ve been encouraging us to say No for some time (#56). Saying No is the essence of strategy, of having a focus. Every “yes” is an implicit “no” to all the other things that could have been done during that time or with that energy; it’s best to be explicit about our “no”s. I tried to provide some scripts in #131.

We Can And Must Hold Ourselves to High Standards

Even when we’ve made good choices about what kinds of work to do, it’s up to us, as much as our VPRs or anyone else, to hold ourselves to high standards (#165) for actually doing it well if we’re going to have high research productivity.

We’re the ones who really understand what our team’s potential is, what kinds of impact it could have. For most of our teams, if we’re not holding ourselves up to high standards of impact, no boss will come to tell us to do anything different — but our modest impact will be noted, and any requests for additional funding will be weighed accordingly.

Technical research support standards are rising #161. To keep up we need to make sure we’re learning what works and what doesn’t, incorporating that into modest amounts of process and automation (#95), which increases our leverage and helps us get reproducibly strong results (#157) while letting our team members focus on the creative parts of the work.

Uncertainty And Long Time To Payoff Is Not An Excuse

None of this means we need to think only in the short term; nor am I living in a fantasy world where you turn some crank and then deterministically out pops some high-impact paper.

Research is a long game. Helping some junior new faculty member (or a faculty member new to doing computing-power researched) get over the initial barrier to entry to doing a new kind of work might not have any impact this year or next, but could make a huge difference for over the course of five years, for a comparatively modest short-term investment of effort.

And teaching “how to use the cluster” or “use R to analyze data” or software carpentry classes to grad students certainly doesn’t have any immediate research impact, but it can greatly cut down the costs to support trainees over the course of their work.

Yes, the payoff is over the long term, and it’s uncertain. You don’t know if this grad student or this postdoc is going to be the one to have an amazingly successful project. Heck, they don’t know that, either.

But uncertainty and time horizons don’t absolve us from the responsibility of stewardship over the resources entrusted to us. They doesn’t excuse us from having to think judiciously and carefully about how we and our team spends their time, how we marshal our efforts.

Whether in training (#162) or more broadly (#163), it’s up to us to measure and keep an eye on what matters - research impact - and have a plan, a theory of change, as to how our efforts drives that research impact. And to continually update that plan as we learn new things.

The fact that research is hard, uncertain, and slow is more reason, not less, to be thoughtful and careful about planning what work to take on so that we can do the most good.

And you know what? If we’re not sure? Researchers can tell us what has the highest research impact (#158). We just need to talk to them.

Finally, on that note of researchers are the best judge of research impact per unit dollars - Next issue, I’m going to share in some detail my absolutely most cancel-able technical research support opinion. That is: if researchers aren’t even in principle willing to pay what it costs for us to offer a service, we probably shouldn’t be doing it.

With that, on to the roundup!

In the previous issue of Manager, Ph.D. I talked more about the advantages and challenges STEM PhDs have in becoming capable leaders, looking in particular at a paper on (industrial) R&D leadership. Again, we see that there are real, advanced, strengths compared to non-R&D leaders, but weaknesses in some of the basics. But the basics are things we can work on.

The roundup included articles on:

What to Say Next After a Team Setback: Beyond the ‘F’ Word - Karin Hurt and David Dye, Lets Grow Leaders

I like articles by these two for their list of helpful phrases and scripts. Sometimes it’s a lot easier to do the right thing if you have a pocket phrasebook of things to say while doing it.

I’ll offer a categorization for the phrases they suggest:

I think their focus-on-process question is particularly important.

Over in Manager, PhD (#158, #165), but also here (#106, #153) I talk a lot about decision making under uncertainty, which is always the case for us in research (or hiring, or…).

You can’t use the outcome of a decision made under uncertainty to decide whether the decision itself was bad or good. The best decision available under the circumstances will sometimes lead to bad results, or you could luck out with a terrible decision that works well, because there’s so much you don’t know.

What you can do is look at the process that lead to the decision and see if there’s something to be learned there. Was there a relevant source of information that was missed? Was there an assumption that turned out untrue? If so, that’s something that can be used to inform future decisions.

But sometimes you and the team did everything right, and there just were unknown unknowns that tripped you up. It’s no fun at all, but it happens. All you can do in that case is the other stuff — learn, focus on next steps, and make it clear you’re all in it together.

And honestly, a shared fiasco that you and the team handle well together can really improve the team’s mutual trust and esprit de corps. One that’s handled poorly can shred both of those things.

Measuring GitHub Copilot’s Impact on Productivity - Ziegler et al, Communications of the ACM

[disclaimer - my day job right now is working for a company best known currently for making AI hardware, so take this all with a grain of salt. For what it’s worth, though, I started playing with Copilot before joining my current employer, and enjoying it a great deal.]

Whether it’s Copilot per se, or locally hosted models like StarCoder 2 or Code Llama, it’s becoming increasingly clear that these tools are very productivity-enhancing for a lot of kinds of software development, once you get used to using them. Heck, their own internal tool noticeably improved Google developers’ productivity, models have only improved by then (July 2022!), and whatever one might say about Google as a company they are starting from a baseline of extremely capable developers.

A lot of people poke around at tools like Copilot and leave disappointed because their initial impressions are of code suggestions with clear weaknesses. The value of these tools, though, isn’t that it blatts out reams of perfect code for you. From one of the Key Insights listed in the paper:

While suggestion correctness is important, the driving factor for these improvements appears to be not correctness as such, but whether the suggestions are useful as a starting point for further development.

That’s been my experience - in my own personal projects, these tools let me me see and assess starting points much more quickly, and even rapidly mock out a few approaches first to see how they’d look before settling on one.

The other thing is:

The reported benefits of receiving AI suggestions while coding span the full range of typically investigated aspects of productivity, such as task time, product quality, cognitive load, enjoyment [my emphasis added], and learning.

I find these tools just fun, taking coding from being a purely solitary thing and turning it into a conversation with an incredibly eager to please junior colleague who is naive and thinks about things “weirdly” but also occasionally offers surprising insight.

While the authors looked at a number of metrics, the most obvious and seemingly simplistic one, “completion acceptance rate”, seemed to be the most reliable measure for productivity gains, and these numbers seemed to average at around 21%-23%. So even the developers which reported that these tools made them feel subjectively more productive rejected the suggested autocompletions 4 times out of every 5.

The Research Data Services Landscape at US and Canadian Higher Education Institutions - Ruby MacDougall, Dylan Ruediger, ITHAKA S&R

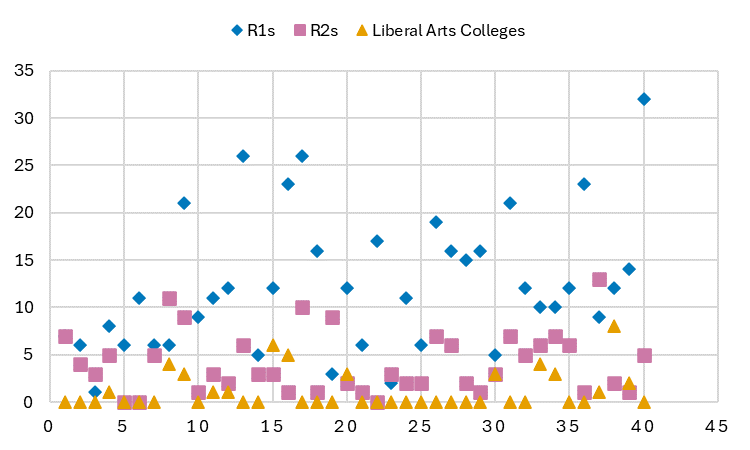

An interesting overview of digital research support services at 120 US and 8 Canadian institutions, through the lens specifically of data services.

One of the things that struck me about this work was the sheer number of services being offered, especially at R1 schools:

That’s north of 30 different services some institutions have, and if you look at the breakdown by providers, it’s about 45% by the libraries, 25% by the research office (I assume that’s digital research support teams under the VPR, but I’m not sure), and then medical schools, IT, and individual academic departments making up the rest.

This explains the authors’ call for greater coordination and collaboration at R1s, and broader support at R2s/liberal arts college, and I agree. Consolidation isn’t the right answer here — no one’s interest is best served by having the management of actively updated (say) single-cell transcriptomics datasets being taken over by the libraries — but with consultation and training making up almost all of the services, there’s a lot of value in making sure that we’re making things easy for researchers while making the best use of every teams’ particular skill sets.

(I also think this is part of a long-term trend as digital-powered research gets both more diverse and more ubiquitous, of increasingly numerous, focussed, and specialized smaller teams cropping up, rather than the one-huge-team-that-does-everything. It doesn’t surprise me that we’re seeing this first and most strongly in data, since as a friend of mine often says, “there’s no such [single] thing as data”. Of course, there’s also no such single thing as research software or research computing, although the community seems to be a little further behind on those realizations).

Finally, it sort of pains me to see how “stats help desk” type services are languishing in this big data age, when statisticians obviously have a lot of useful perspective to bring to a lot of this work.

What Modern NVMe Storage Can Do, And How To Exploit It: High-Performance I/O for High-Performance Storage Engines (PDF) - Gabriel Haas and Viktor Leis, VLDB 2023

Interesting and in-depth paper covering how nontrivial it is to get peak performance is out of NVMe storage. There’s way too much to summarize here, and the discussion is (naturally) focussed on database use rather than (say) local staged-in storage for compute jobs, but I think their conclusions have a lot of useful tidbits for us, including:

This is this newsletter’s second leap year. And while schadenfreude is certainly wrong and beneath us, nonetheless let’s read together a round-up of leap-day bugs.

Google groups has ended Usenet support.

Exploring the slightly nebulous meaning of git’s current branch.

Want to buy your own (emulated) 30 qubit quantum computer? Or a real 3-qubit desktop quantum computer?

Learn postgres in the browser.

The sad tale of Voyager 1 going mad and dying.

(Almost) frying a $500M Mars Rover.

An online electronic connector identifier. GPT in 500 lines of SQL? Sure, that’s cool I guess, but why not GPT-2 in Excel? Maybe that’s how you can apply AI to managing the 20,000 car parts your Formula 1 team needs to keep track of.

As you know, this is principally an embedded database fan club newsletter, so recent embedded DB news - Cloud Backed SQLite, (x2), an embedded ClickHouse OLAP engine, and using DuckDBs JSON support to replace jq. I used jq for something earlier this week, the syntax for anything nontrivial is still baffling to me, should have used this.

And that’s it for another week. If any of the above was interesting or helpful, feel free to share it wherever you think it’d be useful! And let me know what you thought, or if you have anything you’d like to share about the newsletter or stewarding and leading our teams. Just email me, or reply to this newsletter if you get it in your inbox.

Have a great weekend, and good luck in the coming week with your research computing team,

Jonathan

About This Newsletter

Research computing - the intertwined streams of software development, systems, data management and analysis - is much more than technology. It’s teams, it’s communities, it’s product management - it’s people. It’s also one of the most important ways we can be supporting science, scholarship, and R&D today.

So research computing teams are too important to research to be managed poorly. But no one teaches us how to be effective managers and leaders in academia. We have an advantage, though - working in research collaborations have taught us the advanced management skills, but not the basics.

This newsletter focusses on providing new and experienced research computing and data managers the tools they need to be good managers without the stress, and to help their teams achieve great results and grow their careers.

This week’s new-listing highlights are below in the email edition; the full listing of 104 jobs is, as ever, available on the job board.