Success Stories are the best advocacy. Plus: Avoiding hero work pays off in the end; Good progress updates; Design is not recoverable from implementation; Product management at a science tech company; Code-review.org; Configuration shouldn’t change version-controlled source code

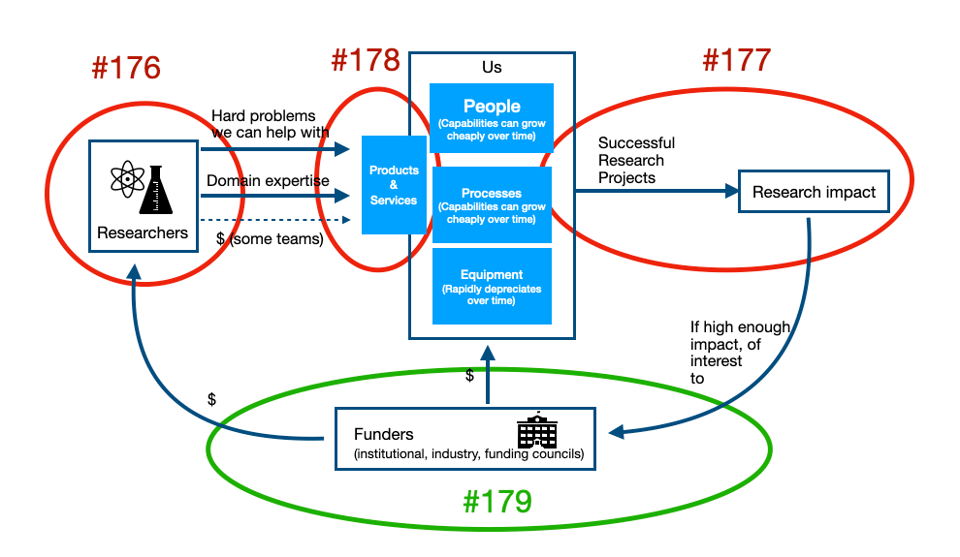

We’re going to continue the series based on this seemingly simple diagram. The diagram sketches out the flywheel of a successful technical research support team, and today I’m going to talk about the part that makes it a flywheel - making sure that the work is noticed by and registers with funding decision makers.

In earlier versions of the diagram, I had the text by the arrow on the bottom right saying “If high enough impact, noticed by…”. That passive voice was a mistake, but it’s no consolation that it’s one made by many teams.

You can’t be passive about having your teams’ impact noticed by others. Not if you want your team to have the success it deserves.

“But the work should speak for itself…” - No! That’s what people say when they don’t want to put in the effort of speaking on behalf of the work and the people who do it. Work does not speak. Work does not advocate. People speak. People advocate. People show how their work benefits others.

And if we care about our team and the work it’s doing? Then I have terrible news, but “people” has to be us.

Those who decide on funding for our teams don’t understand the work we do, nor have any sense of how well we’re doing it (#165). It’s up to us to demonstrate the scientific impact our work is having.

We operate as a professional services firm (#127), but that’s not our business model. If it was, nearly all we would have to do is keep our existing clients happy so they come back for more work. If we want to grow, sure, we have to market our services, but we can operate at near steady-state by picking up the occasional new business here and there.

Instead, our business model is that of a nonprofit (#164). (This is typically true even for the teams that do a fair amount of fee-for-service business, as they are still subsidized). We have primary clients — the researchers whose work we supercharge — and our sustaining clients, who are the national and institutional funders and decision makers.

In such a business model, even treading water and maintaining a steady amount of funding requires consistent advocacy and communications. (Just ask your researchers!)

The people giving money to us have very limited means, compared to the needs; and are faced with an effectively unlimited number of perfectly worthy targets for their money. They are constantly approached by people who have good and worthwhile and exciting proposals, people who are genuinely convinced, with some supporting evidence, that this proposal is the most valuable thing that could possibly happen at the institution. All of this is happening while budgets are getting tighter, not more generous, on average.

In this situation, we owe it not just to our team but also to the decision makers to show them exactly how our team advances the goals they have. If we don’t do that job, a job that really only we can do, how can the decision makers possibly make informed decisions about how they should best assign funds? And without us, who is there to trumpet the amazing work our team does?

Whether we’re talking to program officers or someone in OVPR or OCIO, the communication and advocacy we’re going to be doing is simply having an iteratively more effective series of conversations.

And these will be conversations, not emailed documents. I know you love the documents you assemble, they’re awesome, but they’re not getting read.

More importantly, though, you don’t learn things by sending people PDFs. And in these conversations, we’ll be learning as much from them as they are from us - we’ll be asking them what is important to them, what problems they’re having that perhaps we can be enlisted to solve. And we’ll be sharing with them the work we do, with a spotlight on exactly those problems or important opportunities.

Over time you’ll learn exactly who is interested in what, but you can begin from a pretty solid starting point.

I can tell you for absolute certain that your decision makers do not inherently care at all about any of the following:

They may even ask for those things, but only because they have no other idea what to talk to you about, or because your predecessor showed them those numbers and now they’ve became trained to expect them. But if they think those numbers are all your team has to offer, they won’t value your team very highly.

If your decision makers start digging deeply into those numbers and start asking why they’re low, they think your team is doing a bad job and just don’t know any other way to ask probing questions. If your decision makers think you’re doing well, then they will forget these numbers before they’re even finished reading them.

Either way, every minute you spend talking about these numbers with your decision makers is a minute you’re not talking about something matters, and not demonstrating to them that you and your team realize what matters.

I know this, and you know this, gentle reader; and yet, I can’t tell you how many times I’ve spoken in the last couple of years with people, asking them how they think of the impact of their teams, and had them go blank for a second before answering something about utilization rate or number of jobs or numbers of tickets. Even in this common era year two thousand twenty four, we have work to do as a community.

Those numbers are not important. The things they count are not inherently valuable. You can juice utilization rate or number of tickets or number of clients by breaking tickets into dozens of little sub-tickets or giving busy work to your computers or people or expending resources offering near valueless services to massive numbers of people; not only do those things not advance science, they hinder it in annoying little paper-cut ways. You can drop those numbers while making your community’s research environment better by having very long running collaborative discussions, by leaving staff time available for professional development or computer time available for high-priority jobs, or by focussing on the research sub-communities where your team can do the most good.

Those numbers being high or low says nothing about the reason our teams exist, which is advancing our community’s research as much as possible given our constraints.

Your decision makers have specific problems they’re trying to solve and are willing to allocate money to solving those problems (#75). Focusing on institutional decision makers: at small institutions, it’s often about trying to nucleate a critical mass around certain interdisciplinary areas. In larger institutions, it might be about trying to develop capability in a new area, or maintaining a lead in an established field of expertise, or making sure that new faculty members are given the support they need to launch their careers successfully.

Your decision makers care somewhat, in an abstract sort of way, about number of papers that relied on your team’s support. But not all papers are equally valuable, your contribution to any given paper much less the sum of them is unclear, and your decision makers care about specific areas and researchers more than others.

Your institutional decision makers care more strongly about total amount of grant funding projects you’re supporting are bringing in. Decision makers of any sort will be impressed by the total amount of grant funding where your team is explicitly written into the grants, because that’s an unmistakeable endorsement stating that funding your team is a cost-effective way of advancing research (#178), given by the people who care more than anyone else about that research.

Decision makers will also be interested in how you’re working successfully with other teams (because other teams are not the competition, less and worse science is - #142 - and because this shows canny and effective use of resources).

But nothing is really going to compete with success stories and testimonials, curated to the interests of the person you’re speaking to.

This is hard for us to accept; our training focussed on quantitative data. Plots! Error bars! Equations!

But an actual story, describing in detail about how your team in particular made possible some important-to-the-listener advance by a named and quoted researcher, answers more questions about the impact your team brings to your community than any plot or table you can show.

Collecting these stories is time- and labour-intensive; but the conversations you have collecting them are inherently valuable, and you’ll learn a lot; the materials you collect can be reused countless different ways; and they are compelling to decision makers and other researchers, while documenting for your team members why what they do matters and giving them a portfolio of their contributions. You can use them in talks and on your website and in annual reports and in emails. Eventually you have a library that can be deployed in a targeted way as needed.

So my recommendation here is simple, but not necessarily easy — start talking with your stakeholders and decision makers; find out who cares about what, and what problems they’re trying to solve; collect quantitative data, sure, but also qualitative data in the form of success stories and testimonials about the impact your team has; and share that information relentlessly with the people who will care the most, while learning what does and doesn’t work.

So that completes our loop around our flywheel diagram. The next issue or two will focus on the “us” box - I’m leaving that for towards the end, because it only makes sense to talk about operating the “us” box after establishing the context of the whole flywheel.

Until then, on to the roundup!

Across the way over at Manager, Ph.D., last week I talked about something particularly important for our inherently very interdisciplinary and cross-organizational teams: how managing up (and sideways, and diagonally) is part of our job.

In the roundup I covered articles on:

Avoiding hero work pays off in the long run - Ben Cotton, Duck Alignment Academy

I talk to a lot of technical research support leaders, and I’ve heard more than a few proudly-told stories of teams working heroically, even over weekends, to get something done.

But — we all know that’s not good, right?

Hero work feels good, it’s great to see and feel camaraderie and esprit de corps.

But it speaks to either underinvestment in something, or trying to do something your team is just not equipped to do.

Putting the time and effort and investment into avoiding the need for hero work — or simply declaring some things out of scope given the resources — is at best unglamorous and at worst will get people cross at you.

But as Cotton explains, whether it’s a software release deadline slip or something else, avoiding hero work is an investment in sustained productivity.

How to Send Progress Updates - Slava Akhmechet

When we’re in the weeds of work, it’s easy to forget the larger context and share the wrong information to stakeholders. Akhmechet gives a pretty good list of points to remember about writing effective progress updates, and indeed how the “forcing function” of progress updates can usefully help shape the work being done.

Design is not recoverable from implementation - Eric Normand

Ah, finally a nice succinct way of describing the need for comments, internal documentation, architectural decision records, and the rest: “Design is not recoverable from implementation”.

Our Process - Greg Wilson

Wilson, of software carpentry fame, describes the product management process at “a small to medium sized tech company”:

I believe the most important part of what follows is how she has organized her thinking. Each process exists to answer key questions, has its own frequency, is someone’s responsibility, and generates specific products.

That observation is really important - processes need to serve a very clear purpose and have someone who is responsible for ensuring that those purposes are met.

The scale of the team Wilson works on now is probably much larger than any of our teams, and so how those processes are executed might not translate directly, but the basic questions being asked (particularly by things like product & solution discovery) absolutely do, or should.

Code-Review.org: An Online Tutorial to Improve Your Code Review Skills - Helen Kershaw, Better Scientific Software

Kershaw introduces about code-review.org, a series of code reviewing tutorials and blog aimed specifically for scientific code review. This is extremely welcome - congratulations to everyone involved! From the first paragraph of the tutorial introduction:

If you’ll indulge me a 20 year old British comedy reference, a quote from horror writer Garth Marenghi “I’m one of the few people you’ll meet who’s written more books than they’ve read”. Which is a hilarious joke for writers, but a sobering reality for scientific software. It is not that unusual for people working in science to write more code than they read. But we can change that, right?

Apart from making it easier for people to contribute to projects (and accept contributions into projects), thus building more resilient scientific software communities, just getting more research software developers reading more code is itself an important goal. This looks promising and I’ll keep an eye on it.

Don’t require people to change ‘source code’ to configure your programs - Chris Siebenmann

The target here is probably more open-source system software than scientific software, but the point stands. Siebenmann argues (and convinces me, at least) that any local configuration should be done in file that won’t be overwritten by installing the next release of the software.

The Zilog Z80, heart of the Sinclair ZX Spectrum, ColecoVision, TRS-80 Models I, II, III, and 4, Dec Rainbow, and early CP/M machines, had been in continuous production since 1976, but is now being discontinued.

The nautical team that keeps the internet working.

A 1985 in-car navigation system that predated readily available accurate GPS, and used a CRT and cassette tapes - the Etak Navigator.

Computational agent-based models have long been used in social science, but this is new - generating hypotheses and automated screening of them with LLMs.

Query your systems like a database.

I find theorem provers fascinating - here’s an intro to theorem proving with Lean 4.

Another interesting declarative diagram drawer - D2.

As more PhD trained scientists leave academia or just choose other paths, companies are setting up to make it easier to spin out science companies. Here’s WilbeLab, which helps set up commercial lab spaces. (Not an endorsement, don’t know anything about this company in particular one way or another, just find the phenomenon fascinating.)

Debian in the browser - we’ve seen things like this before but this is a compelling example of container2wasm.

Automated traversal of networks using SSH private keys - ssh-snake.

A nice discussion of a paper on visualizing uncertainty for non-experts - we can assume too much as experts, it’s an interesting paper and a great distillation.

We’re starting to see papers on teaching coding incorporating AI code-generation tools - super early days, but (unsurprisingly) there are areas of real potential and areas of real gotchas.

Apparently 50 lines is the sweet spot for pull request length.

And that’s it for another week. If any of the above was interesting or helpful, feel free to share it wherever you think it’d be useful! And let me know what you thought, or if you have anything you’d like to share about the newsletter or stewarding and leading our teams. Just email me, or reply to this newsletter if you get it in your inbox.

Have a great weekend, and good luck in the coming week with your research computing team,

Jonathan

About This Newsletter

Research computing - the intertwined streams of software development, systems, data management and analysis - is much more than technology. It’s teams, it’s communities, it’s product management - it’s people. It’s also one of the most important ways we can be supporting science, scholarship, and R&D today.

So research computing teams are too important to research to be managed poorly. But no one teaches us how to be effective managers and leaders in academia. We have an advantage, though - working in research collaborations have taught us the advanced management skills, but not the basics.

This newsletter focusses on providing new and experienced research computing and data managers the tools they need to be good managers without the stress, and to help their teams achieve great results and grow their careers.

This week’s new-listing highlights are below in the email edition; the full listing of 110 jobs is, as ever, available on the job board.